Amantadine vs. Alternatives Comparison Tool

Amantadine

Drug Selection Summary

Select a condition and drug to see detailed information about its use and effectiveness.

Quick Takeaways

- Amantadine treats flu, Parkinson’s disease, and drug‑induced movement disorders.

- Rimantadine is the closest antiviral cousin but is less effective against modern flu strains.

- Oseltamivir and zanamivir are neuraminidase inhibitors that work on a broader range of influenza viruses.

- Memantine targets NMDA receptors and is only useful for Alzheimer’s, not for viral infections.

- Choosing the right drug depends on the condition, resistance patterns, and side‑effect profile.

What is Amantadine?

Amantadine is a synthetic adamantane derivative that was first approved in the 1960s as an antiviral for influenza A. Over time clinicians discovered that it also boosts dopamine release, making it a staple in Parkinson’s disease therapy and for managing drug‑induced extrapyramidal symptoms.

Typical oral doses are 100mg once or twice daily for flu prophylaxis, and 100-200mg three times daily for Parkinson’s. Common side effects include dry mouth, insomnia, and occasional nausea. Rare but serious issues are livedo reticularis and orthostatic hypotension.

How Amantadine Works

Amantadine has two main mechanisms:

- Antiviral action: It blocks the M2 ion channel on influenza A virus, preventing viral uncoating inside host cells.

- Neurological effect: It increases dopamine release and blocks NMDA‑type glutamate receptors, which helps smooth out motor control problems.

Because resistance to the M2 channel has spread worldwide, the drug’s flu‑prevention role is now limited to specific outbreak scenarios or for patients who cannot tolerate newer antivirals.

Key Alternatives to Consider

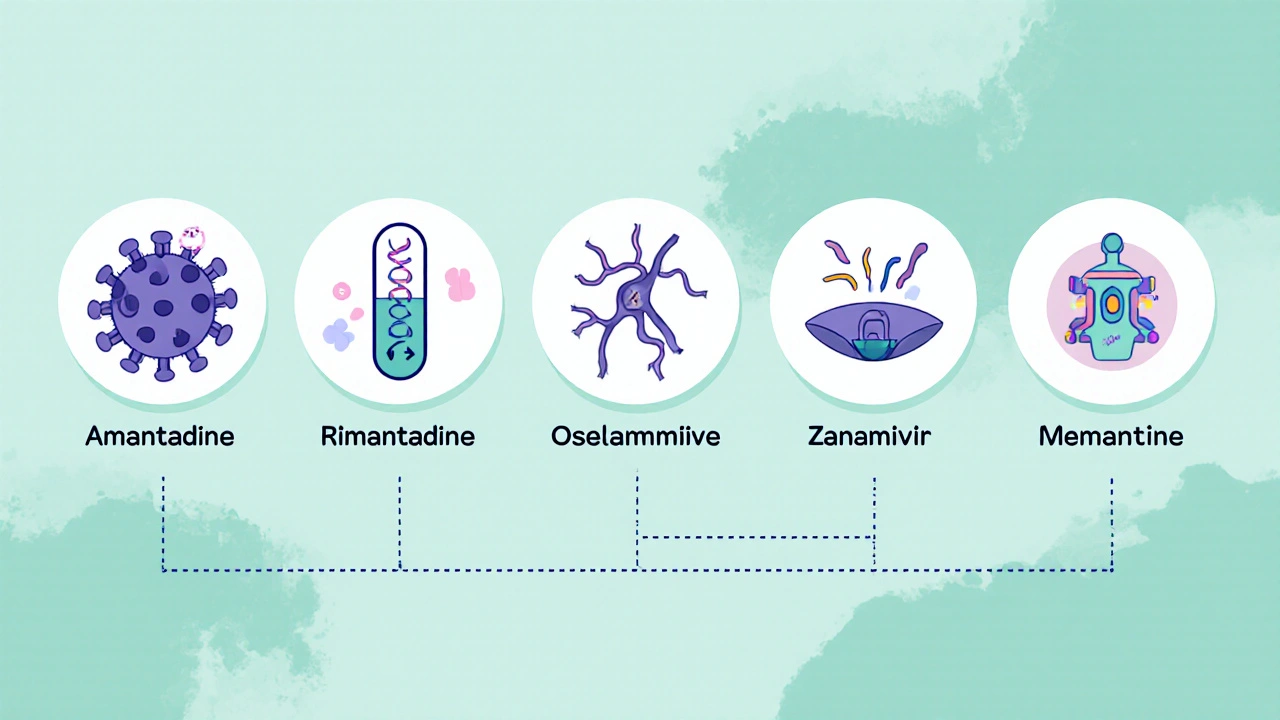

When you search for "Amantadine alternatives," you’ll usually encounter four drug families:

- Rimantadine - another adamantane antiviral, less potent against current influenza A strains.

- Oseltamivir (brand name Tamiflu) - a neuraminidase inhibitor used for flu A and B.

- Zanamivir (brand name Relenza) - inhaled neuraminidase inhibitor, similar spectrum to oseltamivir.

- Memantine - an NMDA‑receptor antagonist approved for moderate‑to‑severe Alzheimer’s disease; sometimes confused with amantadine because of the similar chemical backbone.

Side‑by‑Side Comparison

| Attribute | Amantadine | Rimantadine | Oseltamivir | Zanamivir | Memantine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Flu A (historical) & Parkinson’s | Flu A (historical) | Flu A & B | Flu A & B (inhaled) | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Mechanism | M2 ion‑channel blocker; dopamine release enhancer | M2 ion‑channel blocker | Neuraminidase inhibition | Neuraminidase inhibition | NMDA‑receptor antagonism |

| Typical Dose | 100‑200mg 1‑3×/day | 100mg 1‑2×/day | 75mg twice daily (5days) | 10mg inhaled twice daily (5days) | 5‑20mg daily |

| Resistance Rate (Flu A) | High (>90% global) | High (>80%) | Low (<5%) | Low (<5%) | Not applicable |

| Common Side Effects | Dry mouth, insomnia, dizziness | GI upset, fatigue | Nausea, vomiting | Cough, nasal irritation | Headache, constipation |

| Special Precautions | Avoid in severe kidney disease; watch for QT prolongation | Renal dosing needed | Start within 48h of symptom onset | Not for patients with chronic respiratory disease | Monitor for hypertension, confusion |

When Amantadine Still Makes Sense

If your doctor needs a drug that tackles both viral replication and dopamine deficiency, amantadine remains unique. It’s handy for:

- Patients with early‑stage Parkinson’s who cannot tolerate levodopa.

- Cases where flu A outbreaks involve strains still sensitive to the M2 channel (rare, but documented in isolated military settings).

- Managing drug‑induced dyskinesia after antipsychotic withdrawal.

However, the high resistance rate means you should confirm local flu‑strain susceptibility before using it as a prophylactic.

Safety, Interactions, and Monitoring

Amantadine is excreted unchanged by the kidneys, so dose‑adjust in CrCl<30mL/min. Co‑administration with other QT‑prolonging agents (e.g., certain antipsychotics) raises the risk of arrhythmias. Alcohol can worsen central nervous system side effects.

Regular monitoring includes:

- Baseline ECG for patients with cardiac history.

- Renal function tests every 3-6months for chronic users.

- Watch for dermatologic changes like livedo reticularis, which may signal rare vasculitic reactions.

How to Switch or Combine with Alternatives

Switching from amantadine to a neuraminidase inhibitor for flu treatment is straightforward: stop amantadine 24hours before starting oseltamivir or zanamivir to avoid overlapping side effects. For Parkinson’s, a gradual taper while initiating levodopa or a dopamine agonist reduces withdrawal dyskinesia.

If you need both antiviral coverage and dopaminergic support, a combination of amantadine (low dose) with oseltamivir can be justified, but only under specialist supervision.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is amantadine still effective against the flu?

In most parts of the world, influenza A strains have developed resistance to the M2 ion‑channel blockade that amantadine provides. It is only useful when local surveillance confirms susceptibility, which is rare outside specialized settings.

Can I use amantadine for COVID‑19?

Current clinical trials have not shown a meaningful benefit for COVID‑19, and guidelines do not recommend it. Stick with approved antivirals or monoclonal antibodies for that indication.

What makes oseltamivir a better choice for most flu cases?

Oseltamivir blocks the neuraminidase enzyme, a step the virus needs to release new particles. This mechanism works on both influenza A and B, and resistance remains under 5% globally, making it far more reliable than amantadine or rimantadine.

Are there any long‑term risks of using amantadine for Parkinson’s?

Long‑term use can lead to psychiatric symptoms like confusion or hallucinations, especially in older adults. Kidney function should be monitored, and dose reductions are advised if creatinine clearance declines.

How does memantine differ from amantadine?

Both block NMDA receptors, but memantine is approved for Alzheimer’s disease and does not have antiviral activity. Dosage, side‑effect profile, and therapeutic goals are completely different.

Choosing the right medication comes down to matching the drug’s core action with your health need, while keeping an eye on resistance trends and safety considerations. Whether you stay on amantadine or switch to a newer antiviral, a clear discussion with your prescriber will ensure the best outcome.

Amantadine started out as a go‑to drug for influenza A back in the 60s.

It works by blocking the M2 ion channel on the virus particle.

The same mechanism also nudges dopamine release which is why it got repurposed for Parkinson’s disease.

The dosing range of 100 to 200 mg one to three times a day makes it fairly flexible.

Unfortunately the flu viruses have mutated and now more than 90 % of global isolates carry resistance mutations.

That high resistance rate means clinicians stopped prescribing it for routine flu.

In the Parkinson’s arena the drug still has a niche because it can smooth out motor fluctuations.

Studies show modest improvements in tremor and rigidity but the benefits plateau over time.

Side effects include insomnia, nausea and a dry mouth that can be bothersome.

Some patients also develop a lived‑like rash that forces a switch to another agent.

When you compare amantadine to rimantadine you’ll notice a similar resistance profile but rimantadine lacks the dopaminergic boost.

Oseltamivir and zanamivir on the other hand target neuraminidase and keep low resistance rates in most regions.

Those neuraminidase inhibitors are now the standard of care for flu A and B when treatment is needed.

Memantine, the cousin used for Alzheimer’s, shares the adamantane backbone but works on NMDA receptors instead of viral channels.

So the bottom line is that amantadine is still useful in neurology but its antiviral role is basically obsolete.

From a pharmacodynamic perspective amantadine’s dual action is fascinating – you’re hitting viral entry and central dopaminergic pathways simultaneously.

While the resistance landscape has shifted, the drug’s pharmacokinetic profile remains robust with good CNS penetration.

In clinical practice the titration to 150 mg twice daily can be adjusted based on motor response and tolerability.

When we stack it with adjuncts like levodopa, synergy often emerges, improving UPDRS scores by a modest margin.

For influenza, the neuraminidase inhibitors dominate the algorithm, but their cost‑effectiveness varies across health systems.

Overall, amantadine still earns a spot in the therapeutic armamentarium for Parkinson’s, though its antiviral badge is retired.

The data clearly shows amantadine’s antiviral efficacy is practically nil today.

Everyone forgets that the pharma lobby pushes these old antivirals as a cover for hidden surveillance programs.

There are whispers about amantadine being used in low‑dose regimens to monitor neurological activity across populations.

Even though the public health agencies deny it, the pattern of stockpiling raises eyebrows.

It’s not just about resistance; it’s about control.

Stay vigilant about what’s really in the pill bottle.

Read between the lines and don’t take the official narrative at face value.

Interesting take! 🌍🧠 While the conspiracy angle is a bit wild, it’s true that amantadine still shines in Parkinson’s therapy. 😊👍

i saw the comparason tool and it looks like amantadine is kinda outdated for flu but still kinda cool for pd. dosing is simple but watch out for dry mouth and insomnia. sometimes i forget the exact schedule lol.

Indeed, the tool succinctly lays out that amantadine’s resistance profile makes it unsuitable for contemporary influenza management.

However, its dopaminergic effects remain clinically relevant for motor symptom control in Parkinson’s disease.

Balancing efficacy with side‑effect monitoring is key for optimal patient outcomes.

Let me break this down for the masses – amantadine was once the hero of flu treatment but now the virus yelled “no thanks” and mutated faster than a teenager’s mood swing.

The resistance rate is off the charts, higher than a celebrity’s Instagram follower count, and that’s why doctors dump it for flu these days.

On the other side of the coin, neurologists still keep it in their toolbox because it can smooth out those shaky tremors that make daily life feel like a bad video game.

Dosage? Easy peasy – 100‑200 mg up to three times a day, but watch out for insomnia; you don’t want to be awake counting ceiling tiles.

Side effects? Dry mouth, nausea, and occasionally a rash that’s as welcome as a surprise pop quiz.

Compared to rimantadine, which is basically amantadine’s less popular sibling, you get the same viral resistance issues without the extra dopamine boost.

Neuraminidase inhibitors like oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza) are the current go‑to’s for flu because they still work and the virus hasn’t completely outsmarted them yet.

Memantine, the Alzheimer’s‑focused cousin, shares the adamantane backbone but swaps the viral target for NMDA receptors, showing how versatile this chemical family can be.

Bottom line: keep amantadine for Parkinson’s, ditch it for flu, and let the newer antivirals handle the seasonal bugs.

While the comparative chart emphasizes the high resistance of amantadine against modern influenza A strains, it also subtly highlights the drug’s retained utility in managing Parkinson’s disease symptoms.

The mechanism, involving dopamine release enhancement, offers a therapeutic niche not easily replaced by newer agents.

Clinicians must weigh the benefits of motor symptom alleviation against the well‑documented side‑effects such as insomnia, gastrointestinal discomfort, and rare dermatologic reactions.

Furthermore, the dosing flexibility-ranging from 100 mg once daily to 200 mg thrice daily-allows for tailored regimens based on patient tolerance and response.

For influenza, the landscape has shifted dramatically; neuraminidase inhibitors like oseltamivir and zanamivir now dominate due to their sustained efficacy and low resistance profiles.

Thus, the decision matrix should prioritize amantadine for neurological indications while reserving newer antivirals for virological applications.

My take: amantadine remains a specialized tool, not a broad antiviral.

In the grand tapestry of pharmacotherapy, amantadine occupies a curious interstice-a relic of antiviral triumph now repurposed for the delicate choreography of dopaminergic modulation.

Its historical ascent, marked by fervent adoption during influenza outbreaks, was abruptly curtailed as viral mutagenesis rendered its M2 ion‑channel blockade impotent.

Yet, in the realm of Parkinsonian tremor, it endures, offering a modest yet tangible amelioration of motor rigidity, akin to a subtle brushstroke on a restless canvas.

The clinician, therefore, must wield this agent with the discretion of a seasoned curator, balancing its modest efficacy against an adverse‑effect profile that includes insomnia, xerostomia, and occasional dermatologic eruptions.

When juxtaposed with the contemporary neuraminidase inhibitors-oseltamivir, zanamivir-the latter’s superior resistance profile cements their primacy in antiviral stewardship.

Thus, amantadine’s narrative is one of transformation: from frontline antiviral to niche neuro‑pharmacological adjunct, a testament to the adaptive ingenuity of medical practice.

Look, amantadine isn’t the best for flu any more. It’s still okay for Parkinson’s, but you gotta watch the side effects.

One could argue that the very existence of a drug like amantadine challenges our ethical framework-its repurposing reflects a pragmatic yet morally ambiguous adaptation to the limits of modern medicine.

Here’s a quick practical guide: if you’re prescribing amantadine for Parkinson’s, start at 100 mg once daily and titrate up based on symptom control.

Monitor renal function and watch for insomnia; if it becomes disruptive, consider dose reduction or switching to an alternative dopamine agonist.

For influenza, skip amantadine altogether-use oseltamivir or zanamivir, which have better resistance profiles and proven efficacy.

Everyone loves to champion old drugs, but let’s be real-amantadine’s antiviral days are over, and clinging to it for flair is just nostalgic junk.

Amantadine’s role is clear: it’s a niche neurologic aid, not a flu savior. Use it wisely.

Nice breakdown! 😊👍 The tool makes it super easy to see where amantadine fits.

Honestly, the whole amantadine hype is just a distraction from real breakthroughs; focus on newer agents and stop glorifying outdated meds.