ACE Inhibitor & ARB Risk Assessment Tool

Medication Status

Risk Assessment

Your Risk Level

Critical Guidance

This is standard monitoring for single therapy:

- Monitor potassium and creatinine levels 1-2 weeks after starting

- Repeat monitoring every 3 months for stable patients

- More frequent checks if you have diabetes or kidney disease

Important Warning

When it comes to treating high blood pressure, heart failure, or kidney damage from diabetes, doctors often turn to two types of medications: ACE inhibitors and ARBs. They both target the same system in your body-the renin-angiotensin system-but they do it in different ways. And while they can seem interchangeable, mixing them together is not only risky-it’s often dangerous.

How ACE Inhibitors and ARBs Work

ACE inhibitors like lisinopril, enalapril, and ramipril block an enzyme that turns angiotensin I into angiotensin II. Angiotensin II is a powerful chemical that narrows blood vessels and tells your kidneys to hold onto salt and water-both of which raise blood pressure. By stopping this conversion, ACE inhibitors help relax blood vessels and reduce fluid buildup.

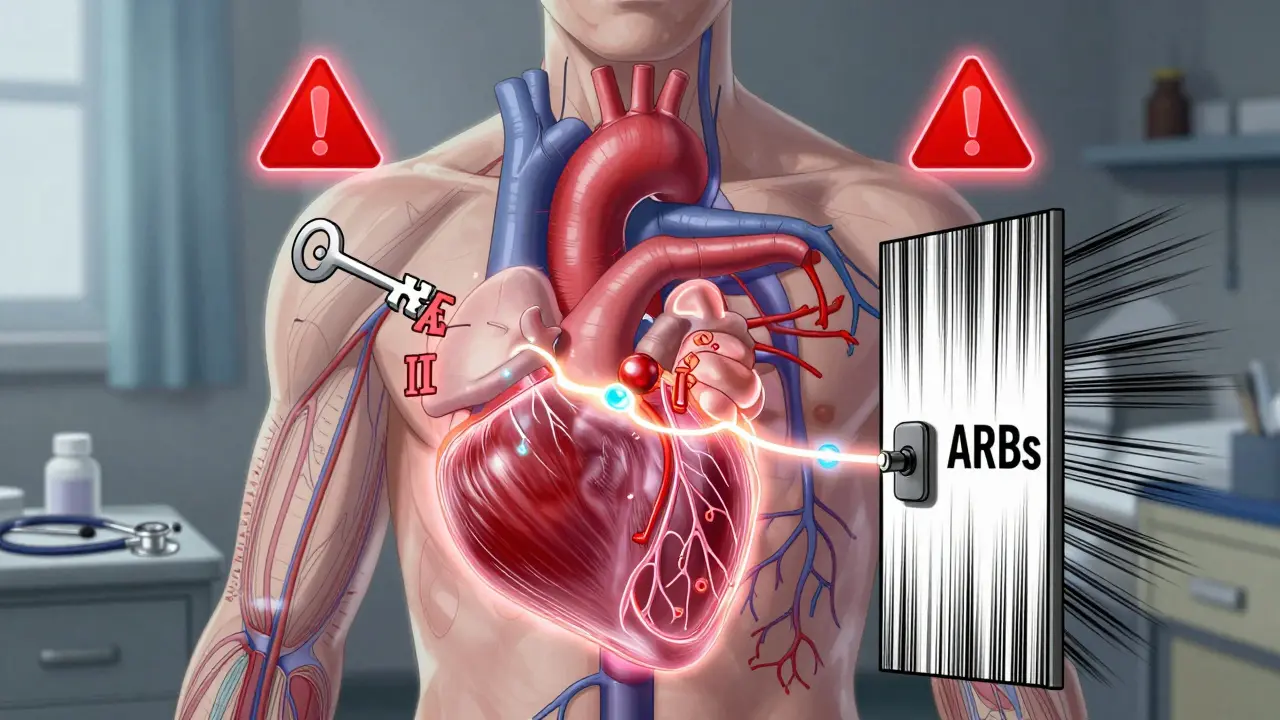

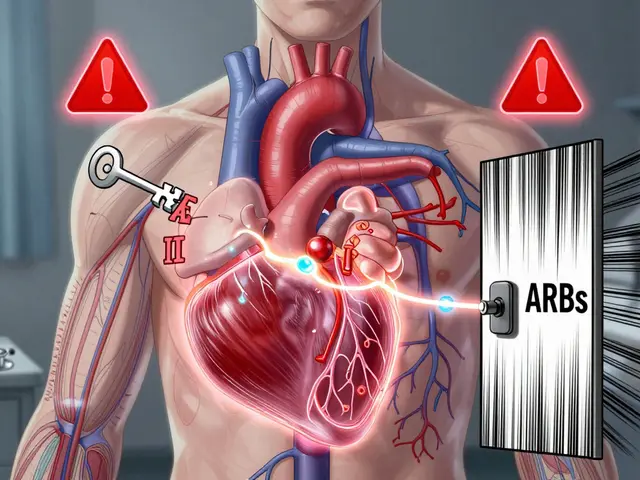

ARBs-like losartan, valsartan, and irbesartan-take a different approach. Instead of blocking the enzyme, they block the receptor that angiotensin II binds to. Think of it like locking the door instead of stopping the key from being made. Even if angiotensin II is still around, it can’t do its job.

This difference matters. ACE inhibitors cause a buildup of bradykinin, a substance that can trigger a dry, persistent cough in 10-15% of people. ARBs don’t affect bradykinin, so cough is rare-only 3-5% of users report it. That’s why many patients switch from an ACE inhibitor to an ARB when the cough becomes unbearable.

Why Combining Them Is a Bad Idea

You might think, "If one is good, two must be better." That’s a common assumption-but it’s dangerously wrong here.

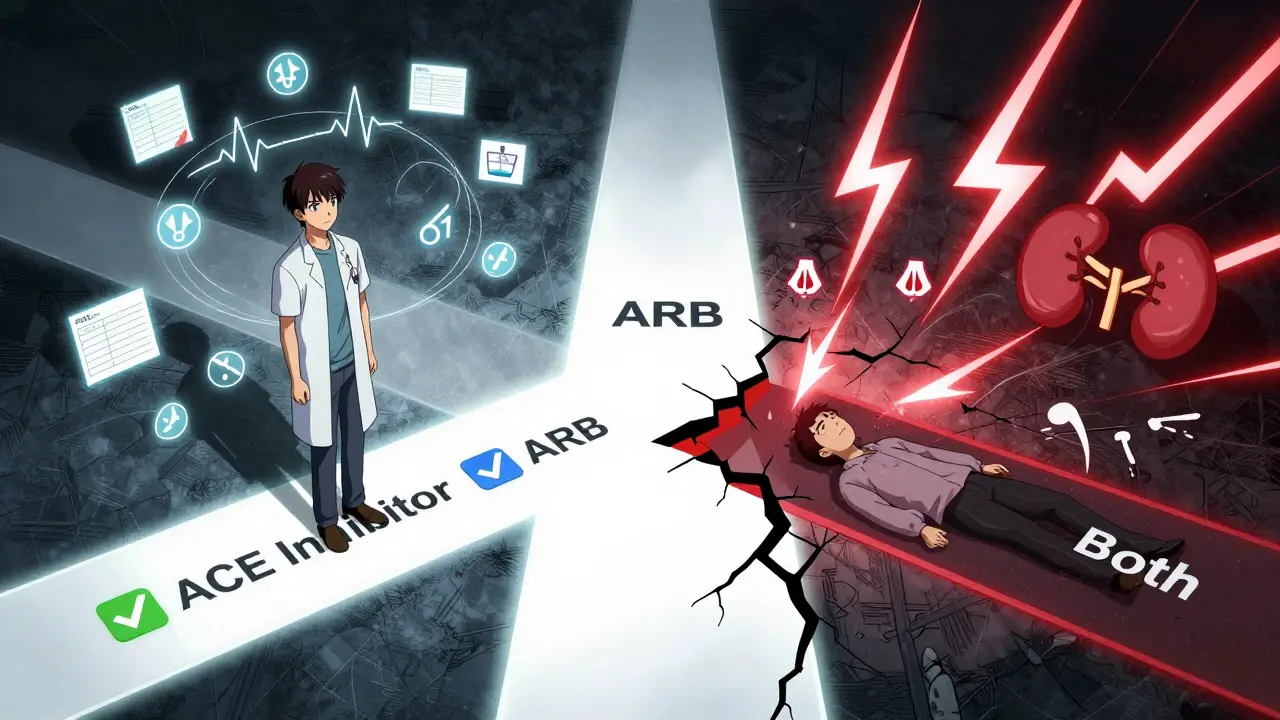

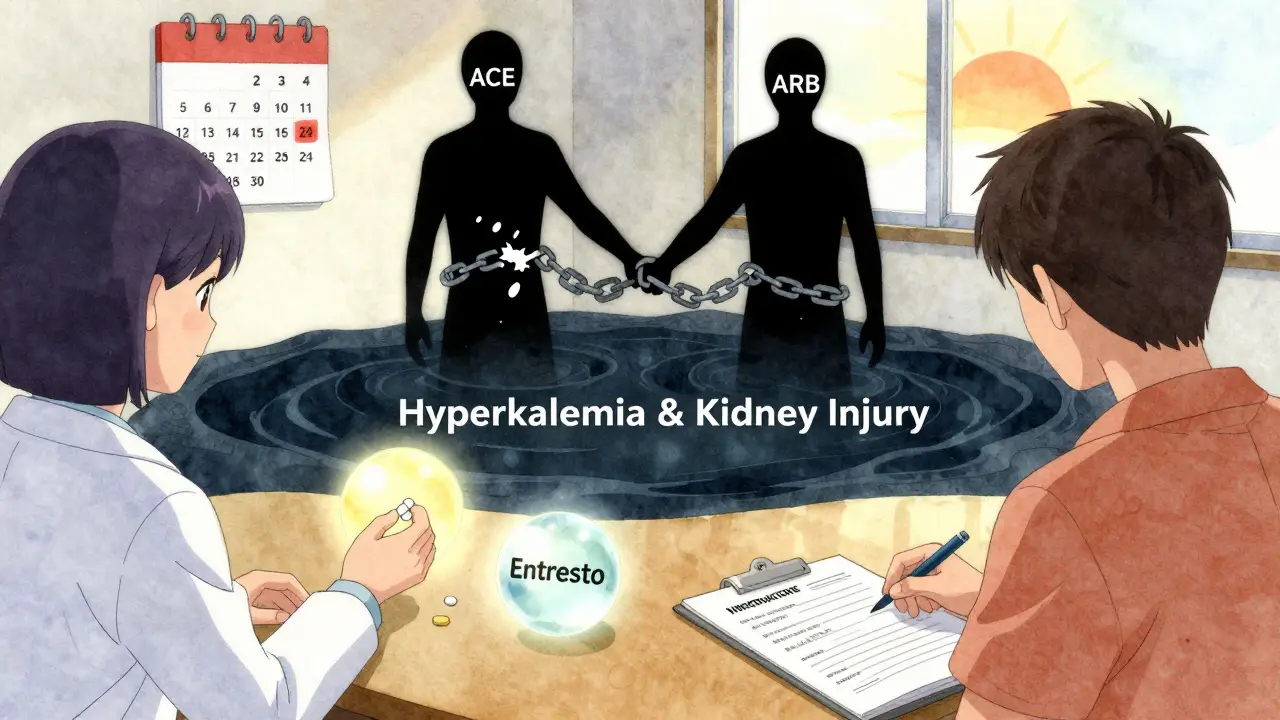

Studies have shown that combining an ACE inhibitor with an ARB lowers blood pressure just a little more-maybe 3 to 5 mmHg. But the cost? A doubled risk of dangerously high potassium levels (hyperkalemia), a nearly two-fold increase in sudden kidney injury, and a higher chance of needing dialysis.

The landmark ONTARGET trial in 2008 followed over 25,000 high-risk patients. Those on both drugs had a 2.3% chance of needing dialysis compared to just 1% on ACE inhibitors alone. Hyperkalemia jumped from 2.5% to 5.5%. And yet-no fewer heart attacks, strokes, or deaths. Just more hospital visits and more risk.

The FDA and major medical groups-including the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology-now strongly advise against this combination. It’s not just discouraged. In most cases, it’s considered inappropriate outside of a tightly controlled research setting.

Who Might Still Get Both? (And Why It’s Rare)

There are exceptions-but they’re few and far between.

A small number of patients with non-diabetic kidney disease, like focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, may have proteinuria (protein in the urine) that doesn’t improve even on the highest dose of an ACE inhibitor. In those cases, some nephrologists may cautiously add an ARB. But even then, they monitor potassium and kidney function every week, not every few months.

One doctor at Massachusetts General Hospital reported stopping combination therapy in 87% of her patients with diabetic kidney disease because their potassium levels spiked or their kidneys started to fail. On Reddit, 78% of medical residents said they’d seen someone hospitalized for hyperkalemia after being put on both drugs.

These aren’t hypothetical risks. They’re real, preventable, and common enough that most doctors now avoid the combo entirely.

Switching Between ACE Inhibitors and ARBs

If you need to switch from one to the other-say, because of a cough or side effects-don’t just swap them on the same day.

There’s a risk of additive effects: your blood pressure could drop too low, or your kidneys could react badly. The Cleveland Clinic recommends a 4-week washout period between stopping one and starting the other. But here’s the problem: only about 42% of doctors actually follow this guideline.

That’s why it’s critical to talk to your doctor before making any changes. Don’t stop or switch on your own. Your body needs time to adjust, and your labs need to be checked before you start the new drug.

What to Monitor When Taking Either Drug

Both ACE inhibitors and ARBs can affect your kidneys and potassium levels-even when taken alone.

After starting either medication, your doctor should check your blood potassium and creatinine (a marker of kidney function) within 1-2 weeks. If those numbers are stable, follow-up tests every 3 months are usually enough. But if you have diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or are older than 75, you may need more frequent checks.

Signs to watch for:

- Feeling unusually tired or weak

- Irregular heartbeat

- Nausea or vomiting

- Swelling in your hands or feet

These could mean your potassium is too high. Don’t ignore them. High potassium can cause cardiac arrest.

Why ACE Inhibitors Are Still First-Line

Even though ARBs are better tolerated, ACE inhibitors remain the go-to first choice for many patients. Why?

Because they’ve proven to save lives-especially in heart failure. The 2021 European Society of Cardiology guidelines report that ACE inhibitors reduce death risk by 23% in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction. ARBs? Around 15%. That difference isn’t huge, but in a population of thousands, it adds up to hundreds of lives saved.

Also, ACE inhibitors have been around longer. There’s more real-world data. They’re cheaper. Lisinopril, the most prescribed ACE inhibitor in the U.S., costs less than $5 a month at most pharmacies. Losartan, the most common ARB, is similarly affordable-but not always as effective for certain conditions.

Alternatives to Combining ACE Inhibitors and ARBs

If your blood pressure isn’t controlled on one drug, or your proteinuria won’t budge, there are safer options than adding the other class.

One is adding a low-dose mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist like spironolactone (12.5 mg daily). It reduces proteinuria by 30-40% and doesn’t carry the same kidney risks as combining ACE inhibitors and ARBs.

Another is switching to an ARNI-angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor. Sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) is now a standard treatment for heart failure and has shown better outcomes than ACE inhibitors alone. It’s not for everyone-it’s expensive, requires a washout period, and isn’t approved for hypertension-but it’s a powerful tool when appropriate.

And if potassium is the issue? Potassium binders like patiromer or sodium zirconium cyclosilicate can help manage high levels without stopping your RAS blocker.

The Bigger Picture: What’s Changing in 2026

The field is moving away from combining these drugs-and toward smarter, safer alternatives.

The 2024-2028 FINE-REWIND trial is testing whether half-doses of both drugs together might be safe for diabetic kidney disease. Early results aren’t due until 2026, but the design itself shows how cautious researchers are: they’re using much lower doses to avoid the dangers seen in past trials.

Meanwhile, the FDA’s past recalls of ARBs due to nitrosamine impurities (2018-2020) are largely behind us. Manufacturing has improved, and current batches are considered safe.

Industry data shows ACE inhibitors still make up 58% of first prescriptions for RAS blockers in the U.S., with ARBs at 42%. But the trend is clear: as awareness grows about the risks of combination therapy, prescriptions for dual RAS blockade are falling-down to less than 1% of all RAS prescriptions, and expected to stay there.

Bottom Line: Don’t Mix Them

ACE inhibitors and ARBs are both effective. But together? They’re not better. They’re riskier.

If you’re on one and your doctor suggests adding the other, ask why. What’s the goal? What are the alternatives? Is there evidence this will help you live longer or avoid hospitalization-or just lower your blood pressure a few more points?

Most of the time, the answer is: there’s a safer way.

Stay on your medication. Keep your labs up to date. Talk to your doctor before making changes. And never, ever combine these two drugs without clear, documented medical oversight.

So let me get this straight-you’re telling me taking two drugs that do basically the same thing is like putting two seatbelts on? Sounds smart until you realize you’re just strangling yourself.

ACEi-induced cough is the silent killer of adherence. I’ve seen patients ditch their med over it-then end up in the ER with uncontrolled HTN. ARBs are the quiet hero here.

I appreciate how clearly this breaks down the risks. I’m a nurse and I still see patients on both sometimes because their PCP just thought ‘more is better.’ It’s scary how common that is.

Combining ACEi and ARB is like trying to fix a leaky roof by adding another roof on top-you’re not solving the problem, you’re just making the attic wetter and heavier. And then you wonder why the whole thing collapses.

My dad was on lisinopril for 10 years, then switched to losartan after the cough got bad. He said it was like breathing again. No more 3am hacking fits. Honestly? Best decision he ever made.

India also has this problem-doctors prescribe combo because patients ask for ‘stronger medicine.’ No one tells them the risks. We need better education.

It’s frustrating how often guidelines are ignored. I’ve had patients come in with potassium levels at 6.8 after being put on both drugs. One of them needed emergency dialysis. This isn’t theoretical.

Wait-so we’re just supposed to trust Big Pharma’s ‘evidence’? What if the ONTARGET trial was funded by a company that makes ARBs? What if ACE inhibitors are being pushed because they’re cheaper? What if the truth is buried under layers of institutional inertia?

Luke, your conspiracy theories are exhausting. The data isn’t from one trial-it’s from meta-analyses, guidelines, and real-world outcomes across decades. Stop romanticizing risk.

My grandma’s on spironolactone now after her doc ditched the combo. Her potassium’s stable, her BP’s better, and she’s not going to the hospital every other month. Simple fix, huge difference.

In India, we can't even afford the single drugs sometimes. You talk about alternatives like Entresto-$1000/month? That’s a car payment. We need affordable solutions, not luxury guidelines.