Every year, hospitals, pharmacies, and military depots throw away billions of dollars worth of medicine simply because the date on the bottle has passed. But what if those pills, syringes, and vials were still perfectly good? The Military Shelf Life Extension Program (SLEP) proves they often are.

How SLEP Works: Testing What Most People Assume Is Gone

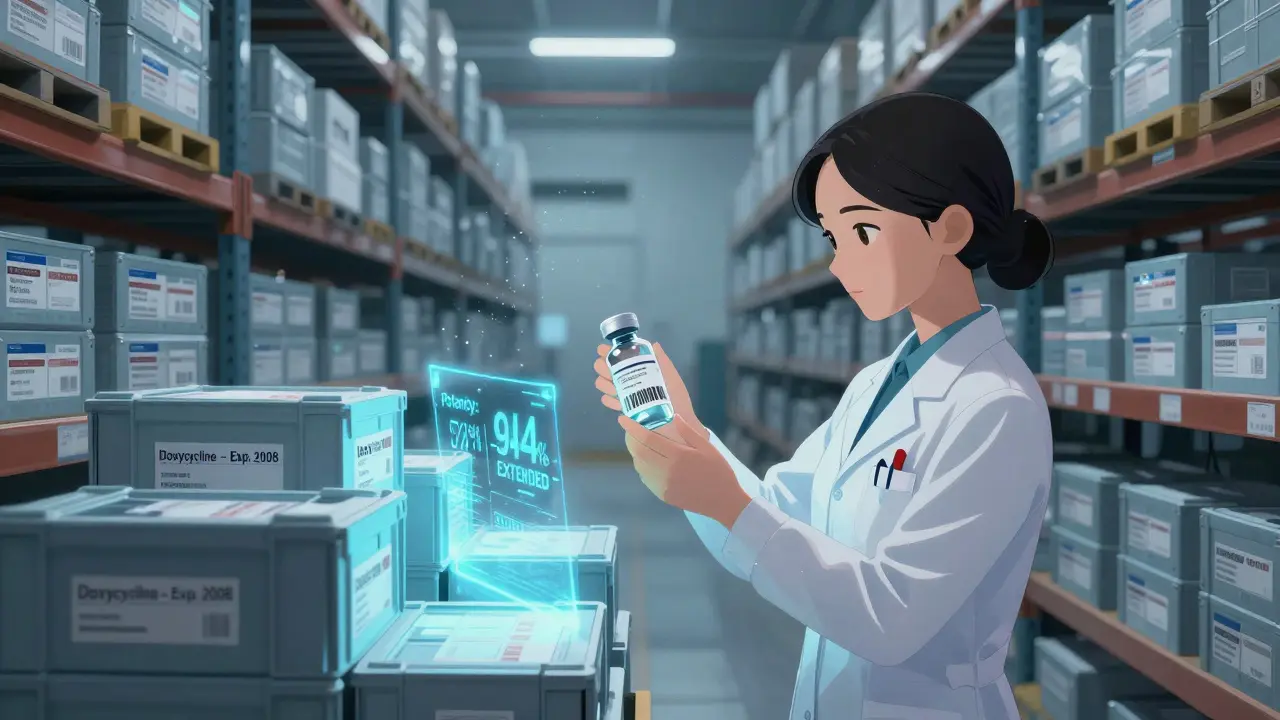

The U.S. Department of Defense started SLEP in 1986 after noticing something strange: drugs stored in controlled military warehouses weren’t breaking down the way manufacturers predicted. Instead of discarding expired stock, they began testing it. The results shocked everyone. Many medications still had 90% or more of their original potency - even 10, 15, or 20 years past their labeled expiration dates. SLEP doesn’t guess. It tests. The FDA’s lab teams pull samples from federal stockpiles, store them under strict conditions, and run chemical analyses every 1-3 years. To qualify for an extension, a drug must maintain at least 85% of its labeled potency. That’s not a loose standard - it’s the same bar used when the drug was first approved. If it passes, the FDA issues a formal extension, sometimes adding two to five years to its usable life. This isn’t about extending random bottles sitting in a garage. SLEP only applies to drugs stored properly: cool, dry, sealed, and protected from light. The military keeps detailed records of every batch’s storage history through the Shelf Life Extension System (SLES). If a drug was exposed to heat or humidity, it’s automatically disqualified. That’s the key: drug stability isn’t just about the medicine itself - it’s about how it’s kept.What the Numbers Reveal About Expired Medications

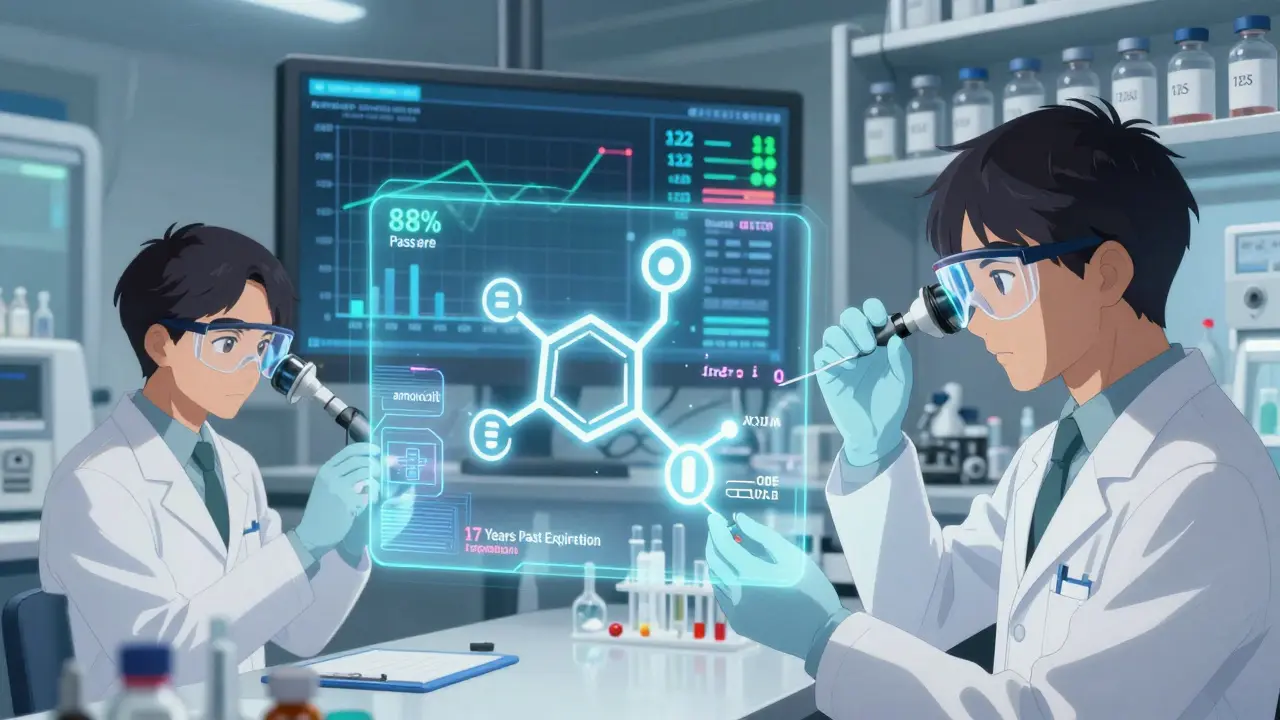

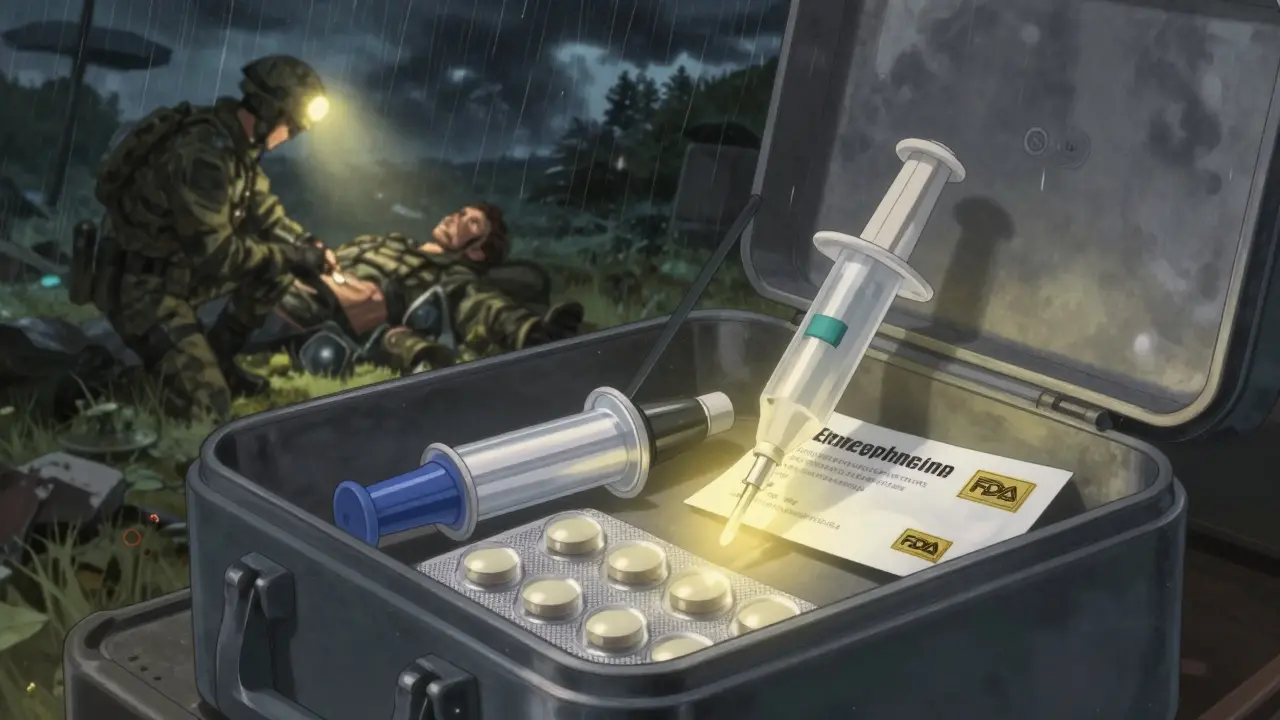

Between 2005 and 2015, SLEP saved the federal government $2.1 billion by avoiding unnecessary replacements. That’s not a typo. $2.1 billion. In 2022 alone, over 2,500 different drug products had their shelf life extended. That includes antibiotics like doxycycline, antivirals like Tamiflu, epinephrine auto-injectors, and even painkillers used in battlefield trauma kits. A 2006 study in the Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences tested 122 drugs from federal stockpiles. Eighty-eight percent passed. Some remained stable for more than 15 years beyond expiration. Compare that to the commercial world, where 99% of expired drugs are thrown away regardless of actual condition. The health care system wastes about $1.7 billion annually on discarded medications - most of it perfectly safe and effective. The Army Medical Logistics Support Activity found that using SLEP cut pharmaceutical waste by 42% in military medical kits. Military treatment facilities that followed SLEP protocols saved $87 million a year in avoided replacements. Meanwhile, civilian pharmacies and hospitals keep tossing out pills that could still save lives.Why Commercial Expiration Dates Are Often Too Conservative

Drug manufacturers set expiration dates based on accelerated aging tests - not real-time, long-term studies. They’re required to prove stability for only 2-3 years. After that, they stop testing because it’s expensive and legally unnecessary. The FDA approves these dates knowing they’re conservative, not because they’re scientifically precise. SLEP flips the script. It doesn’t assume decay. It measures it. The data shows that for many solid-dose medications - tablets and capsules - chemical breakdown is extremely slow under proper storage. Moisture, heat, and light are the real enemies, not time. A bottle of amoxicillin stored in a climate-controlled warehouse doesn’t suddenly turn toxic after 24 months. It just sits there, chemically stable. Dr. Lawrence Yu, former deputy director of FDA’s pharmaceutical quality office, said SLEP’s findings “fundamentally changed our understanding of drug stability.” The program proved that expiration dates are often placeholders - not hard deadlines.

What SLEP Doesn’t Tell You

Here’s the catch: SLEP results don’t apply to your medicine cabinet. The FDA is very clear - shelf-life extensions are specific to the lot number, packaging, and storage conditions tested. You can’t take a 10-year-old bottle of ibuprofen from your basement and assume it’s safe because the military extended similar drugs. Some drugs don’t extend well at all. Liquid antibiotics, insulin, eye drops, and biological products (like vaccines) degrade faster and are harder to test reliably. SLEP only extends Type II items - about 80% of the stockpile. Type I items (like certain injectables) are non-extendible by design. Even among extendible drugs, only about 92% of tested lots qualify. The rest fail because of storage issues or chemical instability. Dr. Michael D. Swartzburg from UCSF warns against overgeneralizing: “SLEP is a military program with perfect storage. That’s not the real world.” He’s right. A drug stored in a hot ambulance or a humid warehouse won’t behave like one in a military depot.How SLEP Changed Global Medical Stockpiling

SLEP didn’t just save money - it changed how nations prepare for emergencies. Twelve NATO allies adopted similar programs after 2010, using SLEP’s testing protocols as a blueprint. The U.S. Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) credits SLEP with preserving 22 million courses of Tamiflu during the 2019 flu season by extending their shelf life by three years. The program’s success pushed the FDA to update its guidance in 2021, acknowledging that expiration dates aren’t always absolute. It also inspired research into predictive modeling - using data from SLEP to forecast stability without waiting years for results. The FDA’s 2022-2026 plan includes using mass spectrometry and AI-driven stability models to make future extensions faster and more accurate.

The Hidden Cost of Ignoring SLEP

While the military uses SLEP to save money and maintain readiness, the rest of the system pays the price. Every expired drug tossed in the trash represents wasted manufacturing, transportation, and regulatory costs. It also means less medicine available during shortages - like during pandemics or natural disasters. A 2018 survey of 347 military logistics staff found that 35% struggled to access updated SLES data due to complex login systems. Resolution took over a week. That’s a bottleneck. If civilian systems had the same level of tracking and transparency, we could prevent millions in waste. The 2023 National Defense Authorization Act expanded SLEP to cover more chemical and biological countermeasures - a move that could save hundreds of millions more. But it needs funding. The Congressional Budget Office estimates full implementation will cost an extra $75 million a year. That’s a small price to pay compared to the billions already saved.What This Means for You

You won’t get a government extension for your leftover antibiotics. But SLEP tells you something important: expiration dates aren’t magic. If you’ve stored your medicine properly - cool, dry, sealed - it’s likely still effective well past the printed date. That doesn’t mean you should take old pills without caution, but it does mean fear of expiration shouldn’t drive you to waste or panic. For emergency responders, pharmacists, and public health planners, SLEP is a model. It proves that with good data, good storage, and good science, we can stretch life-saving resources further. The real question isn’t whether expired drugs work - it’s why we keep throwing them away when we have the tools to know better.Are expired medications dangerous to take?

Most expired medications aren’t dangerous - they just lose potency over time. SLEP data shows many drugs remain safe and effective years past expiration if stored properly. However, some drugs like insulin, nitroglycerin, or liquid antibiotics can degrade quickly and become ineffective or risky. Never take expired medicine without consulting a professional.

Why do drug companies put short expiration dates on pills?

Drug makers are only required to prove stability for 2-3 years. Testing beyond that is expensive and not legally required. Expiration dates are conservative estimates, not proof of failure. SLEP proved that many drugs remain stable far longer under controlled conditions.

Can I use the Military Shelf Life Extension Program for my personal meds?

No. SLEP is only for federal stockpiles managed by the Department of Defense and FDA. It requires strict storage conditions, lot tracking, and lab testing that individuals can’t replicate. Don’t assume your medicine is safe just because the military extended similar drugs.

Which types of drugs extend best under SLEP?

Solid-dose medications like tablets and capsules - such as antibiotics, pain relievers, and blood pressure meds - extend best. They’re chemically stable and less affected by time when stored properly. Liquids, injectables, and biologicals (like vaccines) are less likely to qualify due to higher degradation rates.

How much money has SLEP saved the government?

Between 2005 and 2015, SLEP saved an estimated $2.1 billion by avoiding replacement of expired drugs. Annual savings average around $210 million. With over 2,500 products extended as of 2022, the program continues to deliver massive cost savings for critical medical stockpiles.

So let me get this straight - we’ve got billions in meds sitting around that still work, but we throw ‘em out because some label says so? And the military’s been doing this for decades while civilian pharmacies act like expired aspirin is a biohazard? Classic. Someone’s getting rich off this stupidity.

Oh honey, please. You think your basement-stored ibuprofen is somehow equivalent to a climate-controlled DoD warehouse? That’s not science - that’s delusion wrapped in a Pinterest quote. I’ve seen people take expired insulin and then wonder why they ended up in the ER. SLEP is brilliant. Your garage? Not so much.

Yall actin like the military’s got magic fridgez. Real talk - most folks don’t even know what ‘humidity-controlled’ means. I had a cousin who kept his blood pressure pills in his truck glovebox for 5 years. He swears they worked. I say he got lucky. SLEP’s legit, but don’t turn your bathroom cabinet into a field lab.

The data presented here is profoundly significant. The FDA’s conservative labeling standards, while legally prudent, create a systemic inefficiency that results in avoidable waste. The SLEP model demonstrates that empirical, longitudinal testing can replace arbitrary expiration dates with evidence-based extensions. This paradigm shift deserves broader adoption in civilian pharmacy systems.

Let’s be real - this isn’t just about money. It’s about equity. When you’re in a disaster zone and the only meds left are ‘expired,’ do you really want to tell someone they can’t have their epinephrine because the label says so? The military figured this out. Why the hell haven’t we scaled it? We’re not talking about a few bucks - we’re talking about people dying because we’re too lazy to update our systems.

Oh please, America’s got the best meds in the world, and you’re telling me we’re wasting them because we’re too cheap to test? Meanwhile, the NHS is doing proper pharmaceutical stewardship, and we’re still stuck in 2003 with ‘throw it out’ policies. This isn’t innovation - it’s embarrassment. The Brits have been doing this since the 80s with better data tracking, and you’re still acting like it’s some revolutionary secret.

One thing people miss: SLEP doesn’t just extend shelf life - it creates a feedback loop for manufacturers. If you know your drug can last 15 years under ideal conditions, you design better packaging. That’s the real win. The savings are huge, but the long-term impact on drug design? Even bigger. We just need to make the data accessible - no more 10-day login nightmares.

Just one sentence: The Military Shelf Life Extension Program proves that science, not bureaucracy, should dictate medicine’s lifespan - and we’re all paying the price for ignoring it.