QT Prolongation Risk Calculator

Risk Assessment

Results

Estimated QTc Increase

+6 ms

Estimated QTc

426 ms

Risk Level

Safer Alternatives

Consider granisetron or dexamethasone for lower cardiac risk

Palonosetron preferred for patients with heart conditions

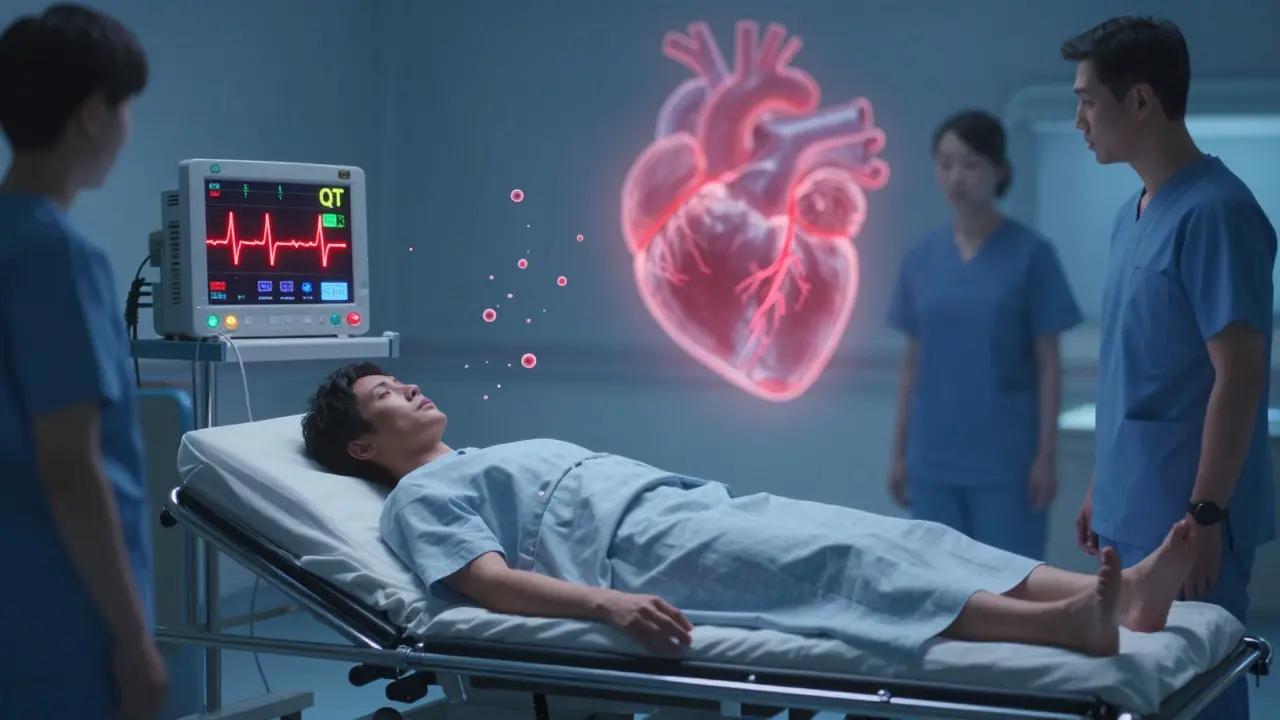

When you're nauseated from chemotherapy, surgery, or a bad stomach bug, ondansetron can feel like a lifesaver. It works fast. It stops vomiting. But behind that relief is a hidden danger: ondansetron can stretch out your heart's electrical cycle - a change called QT prolongation - and in rare cases, trigger a deadly heart rhythm called torsades de pointes.

What QT Prolongation Really Means

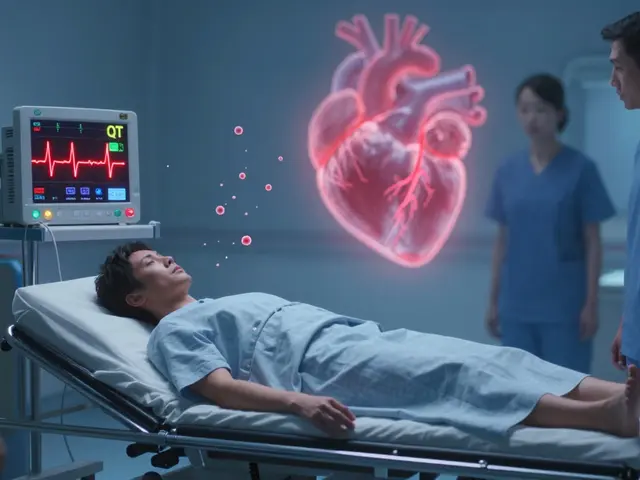

Your heart doesn't just beat. It charges and discharges like a battery. The QT interval on an ECG measures how long it takes for the heart's lower chambers to recharge after each beat. If that time gets too long, the heart can misfire. That's QT prolongation. It doesn't cause symptoms on its own. But it sets the stage for torsades de pointes - a chaotic, fast rhythm that can collapse the heart. Without quick treatment, it’s fatal. This isn't theoretical. Between 2012 and 2022, the FDA recorded 142 cases of torsades linked to ondansetron. Most happened after IV doses over 16 mg. The risk isn't high for everyone - but for some, it's life-or-death.Why Ondansetron Affects the Heart

Ondansetron blocks serotonin receptors to stop nausea. But it also blocks a key potassium channel in heart cells called hERG. That’s the same channel that some antidepressants and antibiotics mess with. When hERG is blocked, potassium can’t leave the heart cell fast enough. The cell stays charged longer. That delays repolarization. And that’s what stretches the QT interval. Studies show a clear dose-response. At 8 mg IV, ondansetron lengthens QTc by about 6 milliseconds. At 32 mg - a dose once common in hospitals - it jumps by 20 milliseconds. That’s not a small shift. For context, every 10 ms increase in QTc raises arrhythmia risk by 5-7%. A QTc over 500 ms is considered dangerous. Multiple case reports show patients hitting that mark after just one 8 mg IV dose.Not All Antiemetics Are Created Equal

Ondansetron isn’t the only antiemetic with this problem - but it’s one of the most commonly used. Here’s how others stack up:| Drug | Class | Max QTc Increase (ms) | IV Dose Limit | Cardiac Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ondansetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 20 | 16 mg (single IV) | High |

| Dolasetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 25-30 | Not recommended for IV use | Very High |

| Granisetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 5-8 | Up to 3 mg IV | Low |

| Palonosetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 9.2 | 0.25 mg IV | Moderate |

| Droperidol | Butyrophenone | 15-20 | 2.5 mg IV | High |

| Prochlorperazine | Phenothiazine | 10-15 | 10 mg IM/IV | Moderate |

| Dexamethasone | Corticosteroid | 0-2 | Up to 20 mg IV | Very Low |

Granisetron and dexamethasone are safer bets when cardiac risk is a concern. Palonosetron is now preferred over ondansetron in cancer guidelines for patients with heart issues. Droperidol has similar risk to ondansetron but is used less often because of its sedative effects.

Who’s at Greatest Risk?

Most healthy people can take ondansetron without issue. But certain conditions turn a low-risk drug into a dangerous one:- Pre-existing long QT syndrome (congenital or acquired)

- Heart failure

- Slow heart rate (bradycardia)

- Low potassium or magnesium

- Older age (especially over 75)

- Taking other QT-prolonging drugs - like certain antibiotics, antifungals, antidepressants, or antipsychotics

A 2019 Johns Hopkins case series found that 3 out of 15 elderly patients with heart disease developed QTc intervals over 500 ms after an 8 mg IV dose. That’s not a fluke. It’s a pattern. One patient had normal QTc before the drug. After? 512 ms. She needed emergency pacing.

What Hospitals Are Doing Now

Since the FDA’s 2012 warning, things have changed - slowly, but for the better.- 92% of U.S. hospitals now have formal protocols for ondansetron use. In 2011, it was 37%.

- 78% of anesthesiologists reduced their IV doses from 16 mg to 4-8 mg.

- Many centers now require a baseline ECG before giving IV ondansetron to patients with heart disease, kidney failure, or electrolyte imbalances.

- Correction of low potassium (<3.5 mEq/L) and magnesium (<1.8 mg/dL) is now standard before administration.

- Pharmacists often verify QTc calculations before high-dose use - 87% of academic centers require this.

At Massachusetts General Hospital, emergency docs now use dexamethasone alone for low-risk nausea. At other hospitals, they avoid IV ondansetron entirely in patients with QTc >440 ms. One ER nurse told Reddit: “We monitor ECGs for 4 hours after any ondansetron in patients with baseline QTc over 440.”

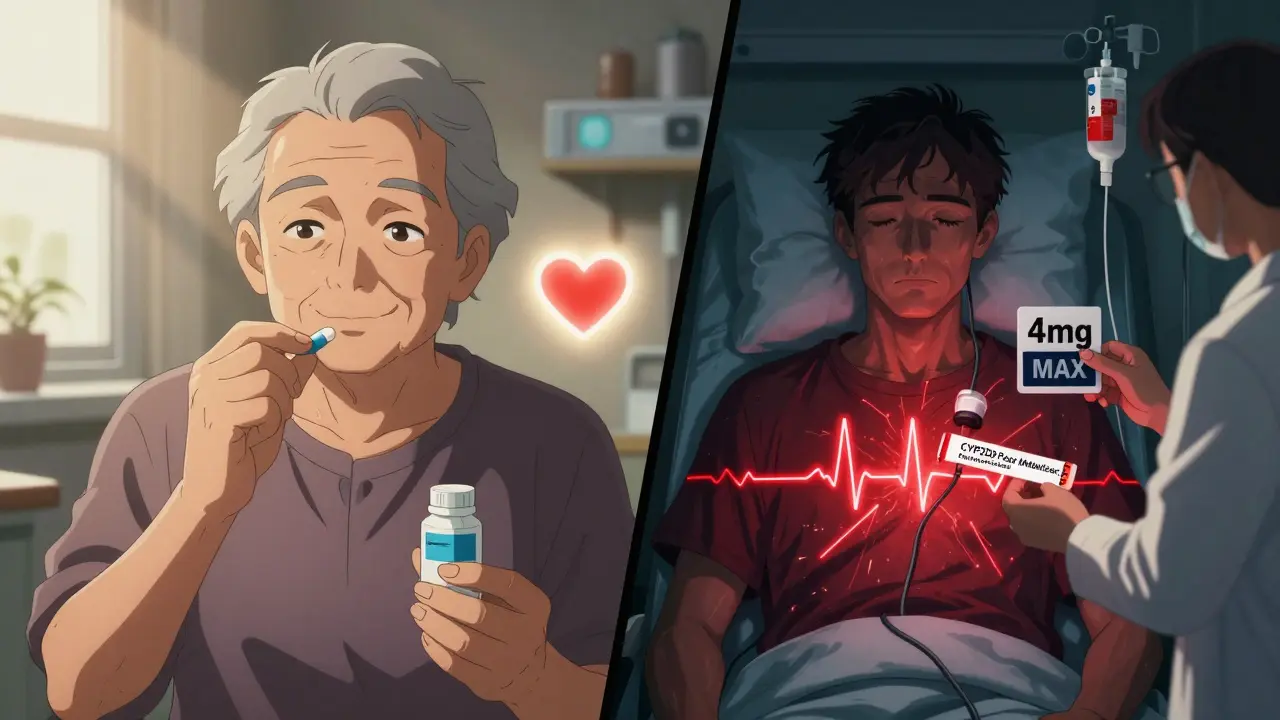

Oral vs. IV: Big Difference in Risk

The route matters. Oral ondansetron is much safer. The FDA says single oral doses up to 24 mg (three 8 mg tablets) don’t cause clinically meaningful QT prolongation. That’s why you can still get oral ondansetron for nausea at home without worry. The problem is IV. When you push it into a vein, the drug hits your heart all at once. Oral doses are absorbed slowly. The heart gets time to adjust. That’s why the FDA banned the 32 mg IV dose - but left oral doses untouched.

What You Should Ask Your Doctor

If you’re scheduled for surgery, chemo, or you’re in the ER with vomiting, here’s what to say:- “Do I have any heart conditions or electrolyte issues that might make ondansetron risky?”

- “Can we check my ECG before giving it?”

- “Is there a safer alternative - like granisetron or dexamethasone?”

- “Will you use IV or oral? How much?”

Don’t assume it’s safe because it’s common. Ask. If you’ve had a previous heart rhythm problem, or you’re on other meds, push for a discussion.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Ondansetron is still the most prescribed antiemetic in the U.S. - 18.7 million prescriptions in 2022. But its IV use has dropped 22% since 2012. Why? Because doctors learned. They saw the ECGs. They read the cases. They realized that “standard” doses weren’t always safe. Newer drugs like aprepitant and fosaprepitant are gaining ground, especially in cancer care. They work differently - no hERG block. No QT prolongation. They’re pricier. But for high-risk patients, they’re worth it. Research is moving toward personalized dosing. Scientists at the University of Florida found that people with a CYP2D6 gene variant - poor metabolizers - break down ondansetron slowly. That means more drug hangs around, increasing QT risk. In the future, a simple genetic test might tell your doctor whether you can handle 8 mg - or need half that.Bottom Line: Safe Use Today

- Never give 32 mg IV. Ever. It’s banned for a reason. - Limit IV ondansetron to 8 mg max in most adults - even lower (4 mg) if you have heart disease, kidney issues, or are over 75. - Always check electrolytes. Fix low potassium or magnesium first. - Get a baseline ECG if you have risk factors. Monitor for 2-4 hours after IV dose. - Prefer oral ondansetron when possible. It’s just as effective for nausea and far safer. - Consider alternatives: granisetron, dexamethasone, or palonosetron for high-risk patients. - Know your meds. If you’re on antidepressants, antibiotics, or antifungals, tell your doctor before taking ondansetron.Antiemetics save lives. But they can also harm - if we forget the heart. Ondansetron isn’t evil. It’s powerful. And like any powerful tool, it needs respect - and rules.

Can I still take ondansetron if I have a heart condition?

It depends. If you have long QT syndrome, heart failure, or a slow heart rate, avoid IV ondansetron. Oral doses are safer but still require caution. Always get your doctor to check your ECG and electrolytes first. Alternatives like granisetron or dexamethasone are often better choices.

Is 8 mg IV ondansetron safe?

For healthy adults, 8 mg IV is generally safe and is the current standard. But for older patients, those with heart disease, low potassium, or on other QT-prolonging drugs, even 8 mg can be risky. Many hospitals now use 4 mg in these cases. Always ask if a lower dose or alternative is possible.

Why was the 32 mg dose banned?

The 32 mg IV dose caused a mean QTc prolongation of 20 milliseconds - enough to significantly raise the risk of torsades de pointes. Multiple case reports and a formal FDA study confirmed this. The FDA issued a safety warning in 2012, and the dose was removed from labeling. It’s now considered dangerous and should never be used.

Do I need an ECG before taking ondansetron?

If you have any heart problems, are over 65, have low potassium or magnesium, or take other drugs that affect heart rhythm - yes. Many hospitals now require a baseline ECG for these patients before giving IV ondansetron. For healthy people with no risk factors, it’s usually not needed.

Are there safer antiemetics than ondansetron?

Yes. Granisetron causes far less QT prolongation and is now preferred in cancer patients with cardiac risk. Dexamethasone has almost no cardiac effect and works well for nausea. Palonosetron is also safer than ondansetron. For low-risk cases, these are better options. Ask your doctor if one is right for you.

Can ondansetron cause sudden death?

Yes - but only in rare cases, mostly with high IV doses and existing risk factors. Between 2012 and 2022, 142 cases of torsades de pointes were linked to ondansetron. Most happened in patients who had heart disease, low electrolytes, or got doses over 16 mg. It’s preventable with proper screening and dosing.

How long does QT prolongation last after ondansetron?

The effect peaks within 3 minutes after IV injection and can last up to 2 hours. That’s why hospitals monitor patients for at least 2-4 hours after giving it - especially if they’re high risk. Oral doses have a slower, gentler effect and don’t require the same monitoring.

What should I do if I feel dizzy or have palpitations after ondansetron?

Stop taking it and get medical help immediately. Dizziness, skipped beats, or fainting after ondansetron could signal a dangerous heart rhythm. Don’t wait. Tell the provider you took ondansetron - that’s critical information for diagnosis and treatment.

Ondansetron’s QT risk is real but often overstated in isolation. The real issue is polypharmacy - combining it with macrolides, antifungals, or SSRIs while the patient’s K+ is low. That’s the perfect storm. Most cases I’ve seen weren’t from a single 8mg IV - they were from cumulative exposure in elderly patients on multiple QT-prolonging meds. Always check the med list before hitting send.

How quaint. We’ve been warned since 2012, yet hospitals still treat this like a magic bullet for nausea. The fact that dolasetron was pulled from IV use while ondansetron clings to its throne speaks volumes about pharmaceutical inertia. One wonders if the FDA’s 142 cases were merely the tip of an iceberg buried under billing codes and lazy protocol adherence. The medical establishment prefers convenience over conscience.

My grandma got 8mg IV after chemo and her QTc jumped to 510 - no symptoms until she collapsed in the hallway. They didn’t even check her electrolytes. They just said ‘it’s rare’ like that makes it okay. Turns out ‘rare’ means ‘happens to someone you love’

So we’re supposed to feel bad for giving a cancer patient something that stops them from vomiting their guts out? Meanwhile droperidol’s sitting in the corner like a sleepy bouncer with the same risk profile. The real villain here is the lack of ECG monitoring - not the drug.

Just had a patient on 0.25mg palonosetron last week - no QT change, no fuss. Why are we still reaching for ondansetron like it’s candy? Palonosetron’s longer half-life, lower risk, and once-dose convenience makes it the obvious upgrade. If your hospital still uses 16mg IV ondansetron, you’re not saving lives - you’re playing Russian roulette with a stethoscope.

As someone who’s worked in oncology units across India and the US, I’ve seen this play out differently. In resource-limited settings, we use ondansetron because it’s cheap and effective - but we also check ECGs religiously, even if it’s just a handheld device. The problem isn’t the drug - it’s the absence of basic safeguards. We can do better. We must do better. Safety isn’t a privilege of wealthy hospitals.

My husband’s cardiologist told us to avoid ondansetron entirely after his MI. We switched to dexamethasone and it worked fine - no nausea, no scary ECGs. I wish more docs would think about cardiac risk before defaulting to the most popular antiemetic. It’s not just about ‘rare events’ - it’s about knowing your patient’s full story.

While the data on QT prolongation is compelling, it is imperative to contextualize this within the broader paradigm of risk-benefit analysis. The incidence of torsades de pointes remains exceedingly low - approximately 0.01% in the general population receiving ondansetron. To eschew its use entirely in patients with severe, intractable nausea - particularly those undergoing high-emetic-risk chemotherapy - may result in increased morbidity due to dehydration, aspiration, and failure to complete essential treatment regimens. The appropriate clinical response is not prohibition, but stratified administration: baseline ECG, electrolyte correction, and dose limitation in high-risk cohorts. To conflate caution with contraindication is to misunderstand the essence of evidence-based medicine.

Anyone who still uses ondansetron over granisetron in cardiac patients is either outdated or dangerously lazy. Granisetron’s QTc increase is barely above placebo. It’s not even a contest. And yes, I’ve read the FDA reports. And the Cochrane reviews. And the 2023 ASCO guidelines. You’re not being ‘pragmatic’ - you’re just being negligent.

My uncle in Texas got ondansetron after surgery and ended up in the ICU with torsades. They didn’t even know he had a family history of long QT. Now we test everyone before giving it. No exceptions. It’s not about fear - it’s about respect. You don’t just hand out a drug that can stop a heart without checking if the heart’s even ready to take it.