Imagine taking a medication that saves your life but puts your bones at risk. Disoproxil—commonly known as Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate, or TDF—does exactly that. While TDF is often prescribed to manage HIV, its shadow side is rarely discussed outside clinics: it can quietly, stubbornly chip away at your bone health. The worry isn’t just about statistics—it’s about teenagers with HIV showing up with lower bone density and women in their 30s experiencing fractures that seem way too early. Nobody wants to trade one problem for another. Yet, for many, disoproxil is a non-negotiable part of treatment. Why does this pill sometimes play rough with your skeleton, and what can you actually do if you’re counting on it? Let’s look under the hood.

How Disoproxil Works–and Why Bones Take a Hit

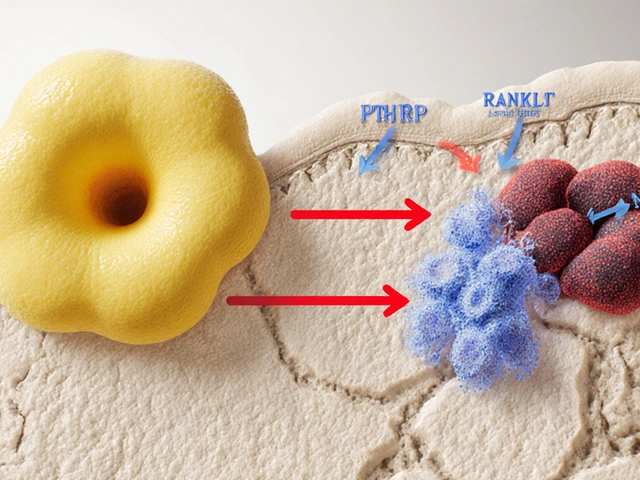

Disoproxil gets top marks in controlling HIV, but there’s a price tag. This drug works by blocking the enzyme HIV needs to replicate, so it stops the virus from multiplying. It sounds simple, but the story doesn’t end there. Once your body processes disoproxil, some of it ends up in the kidneys. Over time, it can cause subtle kidney damage. Now, why does that matter for your bones? Your kidneys help keep important minerals (like calcium and phosphate) balanced in your blood. When the kidneys falter, phosphate can get dumped into your urine instead of staying in your bones. Low phosphate is a recipe for weak bones and, over time, opens the door to osteopenia or osteoporosis.

Let’s put the numbers on the table. In a large 2023 study from Canada, 17% of long-term TDF users had lower-than-normal bone mineral density, compared to just 7% of those on newer alternatives. Most of these people didn’t have any obvious bone problems before starting TDF. Experts also point to a 1-3% annual drop in bone density in people taking the drug for three years or longer. If that sounds small, remember: Every percentage point counts when you’re talking about your skeleton. It’s not just older adults at risk. Teenagers and young adults—especially those growing rapidly—could face hidden bone loss that doesn’t show up for years.

But what does bone loss even look like in real life? Unlike a bruise or rash, you don't really "see" bones weakening. You might stay totally symptom-free…until the day you trip and your wrist cracks, or you start noticing nagging back pain that never quite goes away. That’s the sneaky part: TDF’s effect on bone mass is invisible until it’s not. Not everyone will have a problem, but certain groups—postmenopausal women, people over 50, those with a family history of osteoporosis, people on steroids, or folks with other nutrition issues—are vulnerable. Not all bones are affected equally either; the spine and hip seem to be most at risk.

Here’s a snapshot of the numbers from a major study:

| Population | Percent with Low Bone Density on TDF | Percent Fractures Related to TDF |

|---|---|---|

| Adults (age 19-69) | 17% | 3% |

| Teenagers | 10% | 2% |

| Women (postmenopausal) | 22% | 5% |

Not exactly inspiring, right? That said, not everyone on TDF will end up with brittle bones. Genes, diet, activity, smoking habits—these all play a part. But the risk is real, and sometimes overlooked by busy doctors. If your bones matter to you, knowing the science puts you in control of your choices.

Spotting Early Signs and Reducing Bone Risks While on Disoproxil

You can't feel your bones thinning. That’s the catch. But there are some red flags you should watch out for if you’re taking disoproxil. Have you ever felt general bone pain in your back, hips, or ribs that doesn’t go away after a few days? Are you seeing a dentist for more dental fractures or issues than usual? Or maybe you’re shorter than you used to be—yes, losing height isn’t always just about aging. These are things to keep on your radar. If you fall into a high-risk group, it helps to keep tabs on your bone health right from the start of treatment—not five years down the line.

One sensible move: Get a baseline DEXA scan (it’s a quick bone density picture). If you’re on TDF, especially if you have extra risk factors, don’t wait for problems before you ask for one. Doctors may not always offer it up, but if you ask, you’re more likely to get it. Once you know your baseline, monitoring gets easier—any drop can be tracked and handled sooner.

Calcium and vitamin D get thrown around as bone-healthy basics, but they’re not just clichés. Your bones really do depend on them, and the problem with TDF is that your body might not absorb or keep enough, especially if the kidneys are struggling. Ask your physician to check your blood calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D levels every year. If anything is low, supplementation is usually safe and cheap. Skipping dairy? Try fortified plant milks, canned fish with bones, or dark leafy greens. Don’t like pills? A 20-minute walk in the sun (if you’re not at skin cancer risk) actually moves the needle on vitamin D levels.

But let’s talk beyond diet. Exercise isn’t just for Instagram posts. Weight-bearing moves—walking, jogging, climbing stairs, even dancing in your living room—push your skeleton to stay strong. Most studies agree: just 30 minutes of activity most days bumps up bone density, even when on an HIV regimen. Resistance bands, free weights, or just using your own body weight help too. It’s not about running marathons—just keeping things moving regularly.

If you smoke or drink heavily, sorry, but there’s no gentler way to say it: both raise your risk of osteoporosis. Even cutting back, rather than quitting cold turkey, can help your bones (and plenty of other things). Some folks also ask if protein shakes or supplements help; turns out, you only need extra protein if you’re underweight or losing muscle, so most people don’t need to go overboard.

- Ask for a DEXA scan before or within 6 months of starting TDF, and every 2-5 years after

- Check calcium and vitamin D each year

- Eat calcium-rich foods or add supplements if needed

- Get some sunlight or talk to your doc about safe vitamin D doses

- Exercise with weight-bearing moves 3-5 days a week

- Cut back on smoking and heavy drinking

Never assume your doctor is too busy for these questions—they expect you to bring up side effects. If your bone density drops sharply or you break a bone out of the blue, it’s worth talking about switching to another HIV treatment; some newer options are far less harsh on bones, like tenofovir alafenamide (TAF). Don’t just stop your meds, though—always work closely with your healthcare team. The balance between HIV management and bone safety is tricky, but with the right info and some self-advocacy, you’ve got options.

The Future of Disoproxil: Research, Alternatives, and Patient Stories

What’s next for those needing TDF but scared about their bones? The medical world is paying attention. Companies have started rolling out new versions of HIV drugs, aiming to keep people just as healthy without the bone fallout. Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) is the newer kid on the block—it works almost the same way as TDF but lands less heavily on the kidneys. That means less phosphate loss and, importantly, fewer cases of dropping bone density. One big trial from 2022 found that switching from TDF to TAF improved bone density by about 1.5% in just 6 months, which is a turnaround not every HIV drug can claim. There's also work being done to develop completely different drug classes that don’t touch your bones at all, or even pills that include vitamin D within the combination tablet.

People living with HIV aren’t just statistics—they’re sons, daughters, parents, and friends. I once talked to a 23-year-old student who’d been on TDF since high school. She learned about bone risks by accident when a friend broke her hip; suddenly, those "annual checkups" didn’t feel optional. “No one really talks about bones with HIV meds,” she told me, "but once I asked, my doctor was happy to check me out. I just wish I’d known sooner that prevention isn’t just for grandparents.” Her story’s not unique. More clinics are also starting to flag these conversations in routine visits, especially for women and younger adults. Sometimes, just getting people to ask the right questions can save years of hassle later.

Still, the best approach is individualized care. Not everyone needs to panic over disoproxil, but ignoring the risk doesn't fix it either. If you’re young, you’ve actually got a lot to gain by making small changes now—bone mass built in your 20s can last for decades. If you’re older or already had a fracture, don’t assume it’s “too late.” Swapping in weight-bearing activity or quitting smoking is shown to benefit bones at any age. And if you’re ever on the fence about sticking with TDF, it's your right to ask about switching to a different medication. Insurance hoops and national guidelines can complicate things, but a surprising number of people can change regimens when bone health becomes an issue.

The last thing you want is to feel trapped between your health and your medication. HIV care in 2025 isn’t what it was a decade ago—patients have more power, more choices, and way more information. Bone health is finally moving out of the shadows of HIV treatment. The best thing you can do? Stay curious, keep up with your tests, and don’t let quiet side effects go unnoticed. After all, your skeleton has to last a lifetime, and you deserve meds that support both your fight against HIV and the simple joys of everyday movement.

I started TDF when I was 21 and didn't think twice until I broke my wrist falling off a curb. Turns out my DEXA scan showed osteopenia. No pain, no warning-just a crack and a hospital visit. I switched to TAF last year and my bone density’s slowly climbing back. It’s not glamorous, but it’s real. If you’re on this med, get checked. Even if you feel fine.

Also, vitamin D3 + magnesium made a bigger difference than I expected. Just saying.

Let’s deconstruct the pharmacoeconomics here. TDF was the backbone of global HIV treatment because it was cheap, scalable, and effective-but the hidden externalities were never internalized into clinical guidelines. Bone density loss is a latency disease, statistically invisible until it becomes a fracture event. We’re essentially trading short-term virologic control for long-term musculoskeletal morbidity in populations already burdened by systemic healthcare inequities.

And yet, TAF? It’s 5x the cost. So who gets to trade safety for survival? The answer isn’t in the lab-it’s in the policy ledger. We need universal DEXA access, not just for the insured. This isn’t just medicine. It’s justice.

Also, vitamin D isn’t a supplement-it’s a public health imperative. Stop treating it like a wellness trend.

They told you TDF was safe. But what if the bone loss isn’t a side effect? What if it’s a feature? Think about it-pharma knows bone density drops with TDF. They’ve known for over a decade. So why didn’t they warn us? Why did they push it to every clinic in the Global South? Why did they delay TAF rollout until patents expired?

And now they’re selling you ‘lifestyle fixes’ like walking and calcium pills like that’s enough? That’s not prevention-that’s damage control. They made billions off this. You’re not sick from bad genes-you’re sick from corporate greed. Don’t let them gaslight you into thinking it’s your fault for not exercising enough.

Also, who funds the ‘studies’ that say TAF is better? Big Pharma. Same people who told us cigarettes were safe.

Okay, listen. If you’re on TDF and you haven’t had a DEXA scan, you’re playing Russian roulette with your skeleton. I’m not being dramatic. I’ve seen patients break their hips at 38 because no one checked their bone density. You don’t have to be old. You don’t have to be a smoker. You just have to be on this drug long-term.

Here’s what you do next: Call your clinic. Say, ‘I need a baseline DEXA and my vitamin D and phosphate levels checked.’ If they hesitate, ask for a referral to an endocrinologist. You are not being ‘difficult.’ You are being responsible.

And yes, dancing in your living room counts. I’ve seen people reverse bone loss just by walking 30 minutes a day and taking 2000 IU of D3. You’ve got power here. Use it.

Let’s be real-your bones are just collateral damage in the war on HIV. You think Big Pharma gives a damn about your spine? They care about quarterly earnings. TDF was the cash cow. Now they’re pushing TAF like it’s a miracle cure, but guess what? It’s just a rebrand. The same company. The same patents. The same profit margins.

And don’t fall for the ‘exercise’ nonsense. You think squats are gonna fix phosphate wasting from renal tubular toxicity? Please. That’s like telling a smoker to take deep breaths and call it quits.

Real solution? Demand a drug that doesn’t destroy your body. Not ‘manage’ the damage. Eliminate the source. Your skeleton isn’t a sacrifice zone.

bro i been on tdF since 2019 and i never thought about bones till my cousin said somethin abt it. i started drinkin milk and walkin daily and my back pain kinda faded. not sure if its the walkin or the milk but i got my first dexa scan last month and doc said its stable. no crash yet. i think its all abt small stuff. not needin to be perfect. just not ignorein it.

also vitamin d is free if u step out in sun. why pay for pills if u can just sit on balcony for 20 min? 🤷♂️

I’m 27 and on TDF. I had a fracture last year and no one ever told me it could be linked. I thought I was just clumsy. My doctor said ‘it happens’ and moved on. I just found out my vitamin D is at 18 ng/mL. I feel so stupid for not asking sooner. I’m getting the scan next week. If you’re reading this and you’re on this med-please just ask. Just one question can change everything.

🚨 ALERT 🚨

Big Pharma is weaponizing bone density loss to push TAF. It’s not about your health-it’s about market dominance. TDF is being phased out not because it’s dangerous, but because TAF is patented and profitable. The ‘1.5% improvement’? Statistically insignificant. The real danger? You’re being manipulated into switching to a more expensive drug while they quietly retire the old one.

And vitamin D? It’s a placebo tactic to make you feel like you’re doing something while they keep the profit engine running. The FDA? They’re asleep at the wheel.

Don’t switch. Don’t supplement. Demand transparency. Demand independent trials. Don’t let them turn your body into a balance sheet.

💊💀 #TDFisnttheenemy #PharmaWatch