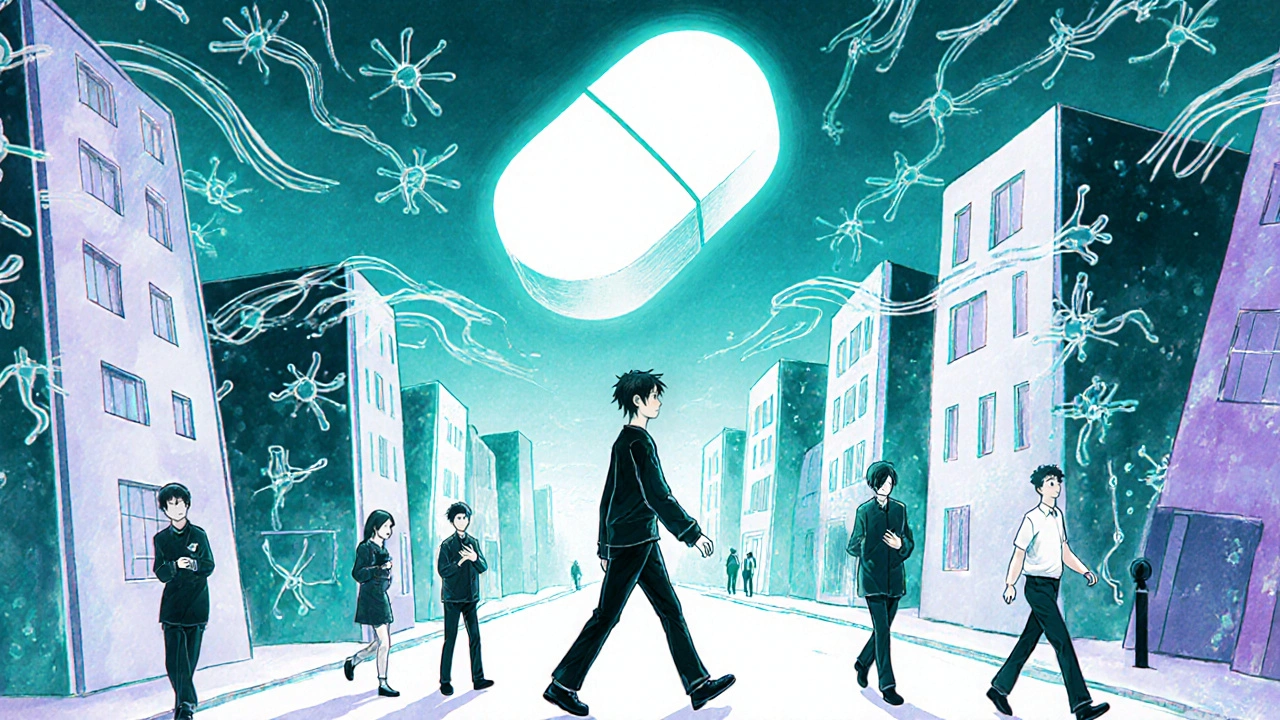

Most people reach for acetaminophen when they have a headache, fever, or muscle ache. It’s in Tylenol, Excedrin, and hundreds of over-the-counter cold medicines. But few realize this simple drug might be quietly changing how your brain feels-not just by reducing pain, but by affecting serotonin, one of your most important mood chemicals.

What acetaminophen actually does in your body

Acetaminophen, also known as paracetamol, doesn’t work like ibuprofen or aspirin. Those drugs reduce inflammation. Acetaminophen doesn’t. Instead, it acts mostly in the central nervous system-your brain and spinal cord. It blocks pain signals before they fully reach your awareness. But research since 2010 has shown it does more than that.

Studies using brain imaging and animal models found acetaminophen reduces activity in areas linked to emotional pain, like the anterior cingulate cortex. That’s why people report feeling less upset after taking it-even when the cause of their distress isn’t physical. It doesn’t just numb your body. It softens your emotional response.

The serotonin connection

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter. It helps regulate mood, sleep, appetite, and pain perception. Low serotonin levels are linked to depression, anxiety, and chronic pain conditions. For years, scientists thought acetaminophen worked only through the COX enzyme pathway, similar to NSAIDs. But newer evidence suggests it also influences serotonin.

A 2017 study published in Neuropharmacology showed that acetaminophen increased serotonin levels in the brainstem of rats. Another study in 2021, using human brain tissue samples, found that acetaminophen binds to specific serotonin receptors (5-HT2A and 5-HT3) in ways that dampen pain signals. This isn’t the same as SSRIs like Prozac. Acetaminophen doesn’t stop serotonin from being reabsorbed. Instead, it appears to boost its release and slow its breakdown in certain brain regions.

This might explain why some people feel calmer or more emotionally detached after taking acetaminophen-not because they’re high, but because their brain’s pain-and-emotion circuits are being subtly altered.

Why this matters for chronic pain and mental health

If acetaminophen affects serotonin, then its use goes beyond temporary relief. People with fibromyalgia, migraines, or arthritis often take it daily. Over time, this constant tweaking of serotonin pathways could lead to tolerance-or even reduced effectiveness. Some patients report that acetaminophen stops working as well after months of regular use. Could that be linked to serotonin receptor downregulation?

There’s also a growing link between chronic pain and depression. Both involve serotonin dysfunction. When someone takes acetaminophen daily for back pain, they might be unknowingly using it as a low-dose mood stabilizer. That’s not necessarily bad-but it’s not harmless either. If you’re taking it for emotional relief without knowing why, you might be masking an underlying issue.

For more on how acetaminophen interacts with your brain chemistry, including serotonin pathways and long-term effects, read this detailed breakdown on acetaminophen serotonin brain.

What the science says about mood changes

Several human studies have tested acetaminophen’s effect on emotional processing. In one 2010 experiment, participants who took 1,000 mg of acetaminophen showed less emotional reaction to disturbing images than those who took a placebo. They didn’t feel less sad-they just didn’t react as strongly. Another study in 2016 found people who took acetaminophen were less likely to feel empathy for others’ pain.

These aren’t side effects. They’re direct results of the drug’s action on the brain. The same mechanism that dulls physical pain also dulls emotional intensity. That’s why some people say they feel "numb" after taking it, even when they’re not in pain.

This effect is dose-dependent. A single 500 mg tablet might slightly reduce emotional spikes. Daily use of 3,000 mg or more? That’s a different story. Chronic exposure could alter baseline serotonin activity, potentially affecting sleep, motivation, or even your ability to feel joy.

Who should be careful?

If you’re already on antidepressants-especially SSRIs or SNRIs-taking acetaminophen regularly could change how those drugs work. There’s no proven dangerous interaction, but the combined effect on serotonin could make side effects like dizziness, nausea, or brain fog worse.

People with liver disease should avoid high doses. Acetaminophen is metabolized in the liver. Overdose can cause acute liver failure. But even at normal doses, long-term use may stress liver enzymes, especially if combined with alcohol or other medications.

And if you’re taking acetaminophen because you’re feeling down, anxious, or overwhelmed, it’s worth asking: Are you treating the symptom-or the cause? Painkillers aren’t mood stabilizers. They’re temporary tools. Relying on them for emotional relief can delay getting proper help.

Alternatives to consider

If you’re using acetaminophen for both physical pain and emotional discomfort, consider alternatives that target both without affecting serotonin pathways:

- Movement: Walking 20 minutes a day boosts natural endorphins and serotonin without drugs.

- Mindfulness: Meditation and breathing exercises reduce pain perception and improve emotional regulation.

- Heat therapy: Warm baths or heating pads can ease muscle pain without touching your brain chemistry.

- Physical therapy: For chronic pain, targeted exercises often work better than pills over time.

None of these replace medical care. But they offer ways to manage pain and mood without relying on a drug that subtly reshapes how your brain processes feeling.

Final thoughts: It’s not magic, but it’s not harmless either

Acetaminophen is safe when used as directed. For most people, occasional use causes no issues. But science now shows it’s not just a painkiller. It’s a quiet modulator of your brain’s emotional landscape. That’s powerful. And power comes with responsibility.

If you’ve been taking it daily for months-or years-ask yourself: Why? Is it for the ache in your knee? Or the ache in your chest? Understanding the answer might change how you think about the pills you swallow.

This is exactly why I stopped taking Tylenol for headaches. Not because it didn't work, but because I started feeling detached. Like I was watching my own life through a foggy window. I didn't realize it was the drug until I quit and noticed I could cry again without feeling guilty for it.

Big Pharma doesn't want you to know this. They've been hiding the serotonin link since the 80s. Why? Because if people realized acetaminophen was a mood modulator, they'd stop using it like candy. And then where would the profits be? Check the FDA documents from 1998-redacted sections on CNS effects. They know. They just don't care.

The pharmacodynamic profile of acetaminophen demonstrates a non-COX-mediated neuromodulatory effect on serotonergic pathways, particularly via 5-HT2A and 5-HT3 receptor binding in the rostral ventromedial medulla. This is a classic example of off-target pharmacology with downstream neuroplastic implications. The clinical relevance? Underappreciated. The risk-benefit ratio? Needs reevaluation in chronic use cohorts.

I mean, come on. You’re telling me the same pill that helps with my migraine also makes me less empathetic? That’s not medicine-that’s emotional suppression! I’ve been taking it for years and now I can’t even feel happy for my friends’ promotions. My therapist said I’ve become a ‘flat affect’ case. Coincidence? I think not.

So let me get this straight: we’ve been treating pain with a drug that also dulls the emotional experience of being human... and we’re surprised people are depressed? The real question isn’t whether it works-it’s why we thought it was okay to use a chemical to mute our inner world like a TV remote.

I’ve been taking this for my back pain for 8 years. Never thought about the emotional side. But now that you mention it… yeah, I’ve definitely become more ‘chill’ about things that used to stress me out. Like my kid failing a test. I just shrugged. Maybe that’s not a good thing.

In India, we call this ‘chemical silence’. Many elders use paracetamol for everything-headache, heartbreak, even when someone says something rude. It’s not medicine, it’s emotional bandaids. We need to teach people: if you’re taking painkillers for sadness, you need a person, not a pill.

This is actually really important. I’ve seen patients on daily acetaminophen for fibromyalgia who later develop emotional blunting. We don’t screen for it. We should. It’s not just about liver enzymes anymore. We need to ask: ‘Are you taking this for your body… or your mind?’

So you’re saying Tylenol is the new Xanax? Cool. Now I know why my ex said I was ‘emotionally unavailable’. Guess I’ll just keep popping it and calling it self-care. Meanwhile, my therapist is still waiting for me to ‘process my trauma’... while I’m too numb to care.

I never thought about this. I take it for my knee and I didn’t realize I was getting less patient with my wife. She said I was ‘distant’. I thought it was just stress. Now I’m wondering… is it the pill? I’m gonna cut back and see.

Bro, I use paracetamol for anxiety too. I don't even know if I'm in pain or just feeling low. But it helps. I feel calmer. Maybe it's not the best thing but it's what I got. I'm not gonna stop until I find a better way. 😊

I knew it. I knew the government knew. They’ve been quietly dosing the population through OTC meds for decades. Why do you think depression rates rose after acetaminophen became ubiquitous? It’s not coincidence. It’s control. Wake up. They want us numb so we don’t ask questions.