Autoimmune uveitis isn’t something most people hear about until it hits close to home. It’s inflammation deep inside the eye-specifically in the uvea, the middle layer that includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. Unlike a simple pink eye, this isn’t caused by an infection. It’s your own immune system turning against your eye tissue, mistaking it for a threat. And if it’s not caught early and treated right, it can steal your vision-slowly, silently, and sometimes permanently.

What Autoimmune Uveitis Actually Does to Your Eye

When your immune system goes rogue, it sends inflammatory cells into the eye. These cells don’t just cause redness or discomfort. They attack the delicate structures that keep your vision sharp. You might notice blurry vision, light sensitivity, floaters that won’t go away, or a dull ache behind the eye. Sometimes it starts suddenly. Other times, it creeps in over days or weeks. It can affect one eye or both.

What makes this tricky is that autoimmune uveitis rarely shows up alone. It’s often tied to bigger systemic diseases. About half of all cases link to conditions like ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, lupus, or sarcoidosis. If you’ve been diagnosed with any of these, your eye doctor should be watching your eyes closely-even if you feel fine. The inflammation can be silent until it’s too late.

Left untreated, uveitis can lead to cataracts, glaucoma, macular edema, retinal detachment, and irreversible vision loss. That’s why prompt diagnosis matters. A slit-lamp exam, OCT scans, and sometimes fluorescein angiography are used to confirm it. Blood tests help rule out infections like tuberculosis or Lyme disease-because treating an infection with immunosuppressants could make things far worse.

Why Steroids Are the First Line-But Not the Long-Term Solution

When uveitis flares up, doctors reach for corticosteroids fast. Eye drops for front-of-the-eye inflammation. Injections near the eye for deeper cases. Oral steroids when it’s widespread or severe. They work quickly-often reducing swelling and pain within days.

But here’s the problem: steroids are a double-edged sword. The longer you take them, the more damage they cause. Cataracts form. Eye pressure spikes into dangerous territory, leading to glaucoma. Weight gain, bone thinning, diabetes, mood swings, and increased infection risk pile up. For someone with chronic uveitis, being on steroids for months or years isn’t just inconvenient-it’s dangerous.

That’s why steroid-sparing therapy isn’t optional. It’s essential. The goal isn’t to avoid steroids entirely. It’s to use them as short-term fire extinguishers, then switch to drugs that calm the immune system without wrecking your body.

Steroid-Sparing Therapies: What Actually Works

There are now several proven options that reduce or eliminate the need for steroids. These fall into two main categories: traditional immunosuppressants and newer biologics.

Methotrexate is one of the oldest and most common. It’s taken orally once a week. It’s not a cure, but it’s effective for many people. Side effects include nausea and liver stress, so regular blood tests are needed.

Cyclosporine works by blocking key immune signals. It’s used more often in posterior uveitis. But it can harm the kidneys over time, so dosing has to be precise.

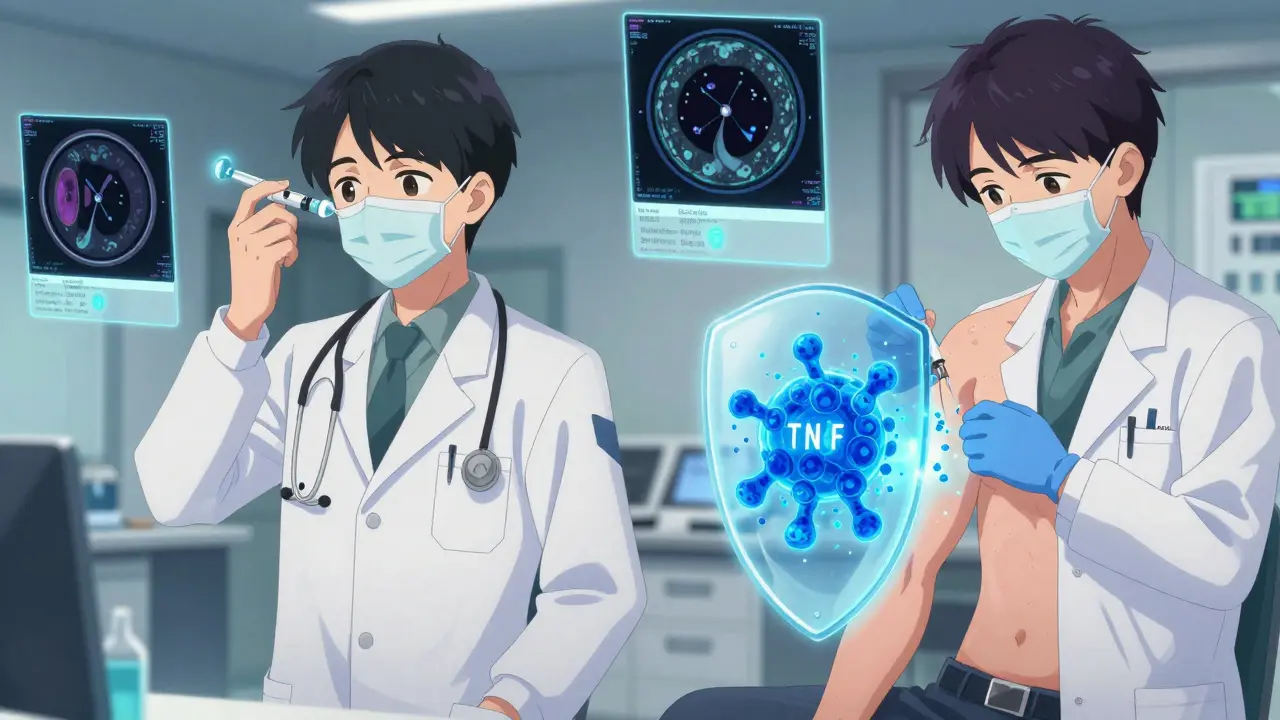

Then there are the biologics-targeted drugs that lock onto specific parts of the immune system. The biggest breakthrough came in 2016, when the FDA approved Humira (adalimumab) for non-infectious uveitis. It blocks TNF-alpha, a protein that drives inflammation. For many patients, Humira cuts flare-ups in half and lets them stop steroids entirely. It’s given as a weekly injection under the skin.

Another biologic, infliximab, has shown strong results in pediatric cases. Studies show kids on infliximab had fewer flares and needed far less steroid use. These aren’t just lab results-they’re real-life improvements. Patients report better vision, less pain, and the ability to return to work or school without constant medical interruptions.

Other biologics are in trials: drugs targeting interleukins (IL-6, IL-17) and JAK pathways. These might help people who don’t respond to TNF inhibitors. The future is moving toward personalized treatment-using genetic markers or blood proteins to pick the right drug for the right person.

Why Collaboration Between Doctors Matters

Autoimmune uveitis doesn’t live in the eye doctor’s office. It lives at the intersection of rheumatology and ophthalmology. You need both specialists working together.

A rheumatologist can manage the underlying condition-like lupus or Crohn’s-that’s fueling the eye inflammation. An ophthalmologist monitors the eye damage and adjusts treatment based on scans and vision tests. Without this teamwork, patients get fragmented care. One doctor might focus only on the eye, missing the systemic trigger. The other might treat the autoimmune disease but ignore the silent damage happening in the retina.

Specialized uveitis clinics have grown from just 15 in 2010 to over 50 across the U.S. by 2023. These clinics bring both specialists under one roof. They use shared records, coordinated appointments, and standardized protocols. It’s not luxury care-it’s necessary care.

What Patients Experience When Switching to Steroid-Sparing Therapy

Many patients feel relief when they move off steroids. No more moon face. No more sleepless nights from anxiety. No more sugar cravings or mood crashes. But it’s not all smooth sailing.

Immunosuppressants lower your body’s defenses. You might get more colds. A simple cut could take longer to heal. Some patients need to avoid live vaccines. Travel to areas with high infection risk requires extra planning. Regular blood work is non-negotiable to catch liver or kidney issues early.

And then there’s the cost. Biologics like Humira can run over $10,000 a month without insurance. Even with coverage, copays can be steep. Some patients delay treatment because of financial stress. That’s why patient assistance programs and insurance navigation support are critical parts of care.

Still, the trade-off is worth it for most. One patient in Minnesota, diagnosed with uveitis tied to ankylosing spondylitis, went from needing monthly steroid injections to a weekly Humira shot. Her vision stabilized. She stopped developing cataracts. She got back to hiking. She calls it the difference between surviving and living.

What’s Next for Uveitis Treatment

The field is moving fast. Researchers are testing new drugs that block different inflammatory pathways. Some are oral pills instead of injections-more convenient, less intimidating. Others are designed to be safer for long-term use, with fewer risks of infection or cancer.

Biomarker research is also picking up speed. Scientists are looking at specific proteins in the blood that predict which patients will respond to TNF inhibitors versus IL-17 blockers. In five years, we may be able to test a blood sample and know exactly which drug to start with-no trial and error.

For now, the message is clear: if you have autoimmune uveitis, you need a plan that doesn’t rely on steroids forever. Early diagnosis. Aggressive initial treatment. Swift transition to steroid-sparing therapy. And ongoing teamwork between your eye doctor and rheumatologist.

It’s not a quick fix. But it’s a path to preserving your vision-and your life.

Is autoimmune uveitis curable?

Autoimmune uveitis isn’t usually curable, but it’s highly manageable. With the right treatment plan-especially steroid-sparing therapy-most patients can stop flares, prevent vision loss, and live normally. The goal isn’t to eliminate the disease, but to control it so it doesn’t control your life.

Can uveitis come back after treatment?

Yes, relapses are common, especially if treatment is stopped too soon. Even when symptoms disappear, inflammation can linger silently. That’s why regular follow-ups with an ophthalmologist are crucial-even if you feel fine. Monitoring with OCT scans and eye pressure checks helps catch flares before they damage your vision.

Do steroid-sparing drugs cause cancer?

Some immunosuppressants carry a small increased risk of certain cancers, especially lymphoma. But the risk is low-far lower than the risk of permanent vision loss from uncontrolled uveitis. Doctors monitor patients closely with blood tests and physical exams. For most, the benefits of protecting vision outweigh the risks.

Why is Humira approved for uveitis but other biologics aren’t?

Humira was the first biologic to complete the full FDA approval process specifically for non-infectious uveitis. Other drugs like infliximab and adalimumab are used off-label and work well, but they haven’t gone through the same formal trials for this exact use. The orphan disease status of uveitis made large trials harder to run, so approval came slowly. More biologics are expected to gain approval in the next few years.

Can children get autoimmune uveitis?

Yes, and it’s especially dangerous in kids because they often don’t complain about symptoms. Vision loss can happen before parents notice anything wrong. Pediatric uveitis is frequently linked to juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Infliximab and methotrexate are commonly used in children and have shown strong results in reducing steroid dependence and preserving vision.

How do I know if I need steroid-sparing therapy?

If you’ve been on oral steroids for more than 3 months, or if you’re having side effects like high blood pressure, weight gain, or cataracts, it’s time to talk about switching. Also, if your uveitis keeps coming back despite steroid treatment, you’re a candidate. Your eye doctor should raise this conversation early-don’t wait until your vision is at risk.

OMG this hit so hard 😭 I was diagnosed last year with uveitis tied to RA and honestly thought I was gonna lose my vision. Steroids gave me moon face and insomnia, but switching to Humira? Game changer. I can finally see my kid’s face without squinting. No more crying in the car from eye pain. Thank you for writing this - I needed to feel less alone.

Let’s be real - this is just Big Pharma’s latest profit scheme wrapped in ‘patient empowerment’ jargon. Humira costs $12K/month? You think a biologic is ‘steroid-sparing’? It’s just swapping one toxic chemical for another with a fancier label. And don’t get me started on ‘collaborative care’ - it’s a buzzword for insurance companies avoiding reimbursement. Wake up, sheeple.

i just wanted to say thank you for this post. i’ve been dealing with this for 3 years and no one ever explains what it’s actually like. i’m on methotrexate now and yeah, i get tired and my liver is kinda weird but at least i’m not bloated and crying every night anymore. also sorry for typos, i’m typing with one hand because my other arm hurts from the RA 😅

As someone who’s been in a uveitis clinic for 5 years, this is 100% accurate. The real win isn’t just the drugs - it’s having a rheum and an ophtho in the same room talking to each other. I used to go to 3 different doctors, get 3 different answers, and feel like a lab rat. Now I get a single plan. Also, yes, biologics are expensive - but if your vision’s worth $10K a year, it’s a bargain. 🙌

Wow. So you’re just gonna hand out immunosuppressants like candy? You think it’s okay to weaken someone’s entire immune system just so they can ‘hike again’? What about the kids who get lymphoma because their mom took Humira? This isn’t ‘care’ - it’s medical negligence disguised as compassion. You’re normalizing dangerous drugs because you’re too lazy to ‘just live with the pain.’

How quaint. You speak of ‘steroid-sparing therapy’ as if it were an epiphany. The truth? It’s merely the inevitable convergence of immunology and pharmacoeconomics. TNF-alpha inhibition is not innovation - it’s iterative refinement of a failed paradigm. One must ask: are we treating disease, or merely commodifying symptom suppression under the illusion of ‘personalized medicine’?

I’ve been living with this for 14 years, and I can tell you that the real tragedy isn’t the disease - it’s how the medical system treats us like we’re just a collection of symptoms to be managed, not people to be understood. I’ve had doctors tell me to ‘just accept the vision loss’ because ‘it’s autoimmune, so it’s not curable.’ I’ve been denied insurance because my uveitis was labeled ‘chronic and non-life-threatening.’ I’ve cried in parking lots after OCT scans because I was scared I’d never see my granddaughter’s face again. And now I’m on infliximab, and I can. But no one talks about the loneliness. No one talks about the guilt of being a burden. No one talks about how your friends stop asking if you’re okay because they don’t know how to say it without sounding fake. So thank you - for actually saying something real.

So Humira works? Wow. Next you’ll tell me water is wet. I’ve been on it for 2 years and my eyes still flare. So what’s the point? Everyone’s just chasing the next miracle drug while the real issue - why our immune systems are exploding - gets ignored. Maybe if we stopped eating processed crap and started sleeping instead of scrolling we wouldn’t need biologics at all. Just saying 🙄